Fifty miles north of Gerlach is one of the prettiest abandoned ranches in Nevada. Denio Camp is as picture-perfect as a painting, alongside a pond set in a wildflower field. The peaceful setting belies its role in the Battle of Kelly Creek, also known as “Nevada’s Last Indian War.” Amazingly, a series of photos depicts Denio Camp and the massacres.

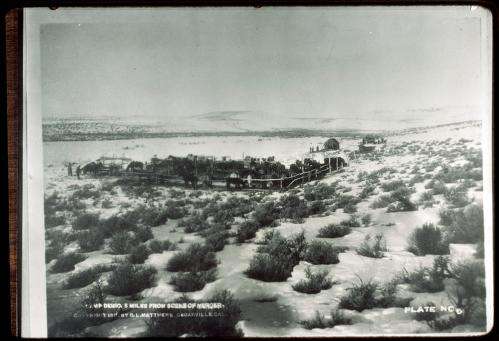

I love it when I uncover little historical treasures. After visiting, I didn’t expect to find an old photo of Denio Camp, but I came across several at the Library of Congress. The title is “Camp Denio, 5 Miles From Scene of Murder, 1911.” The photo was part of a series depicting the Battle of Kelley Creek between Native Americans and law enforcement. Gorgeous scenery, historic buildings and a murder? It was a piece of Nevada history I knew I had to write.

William “Billie” Denio

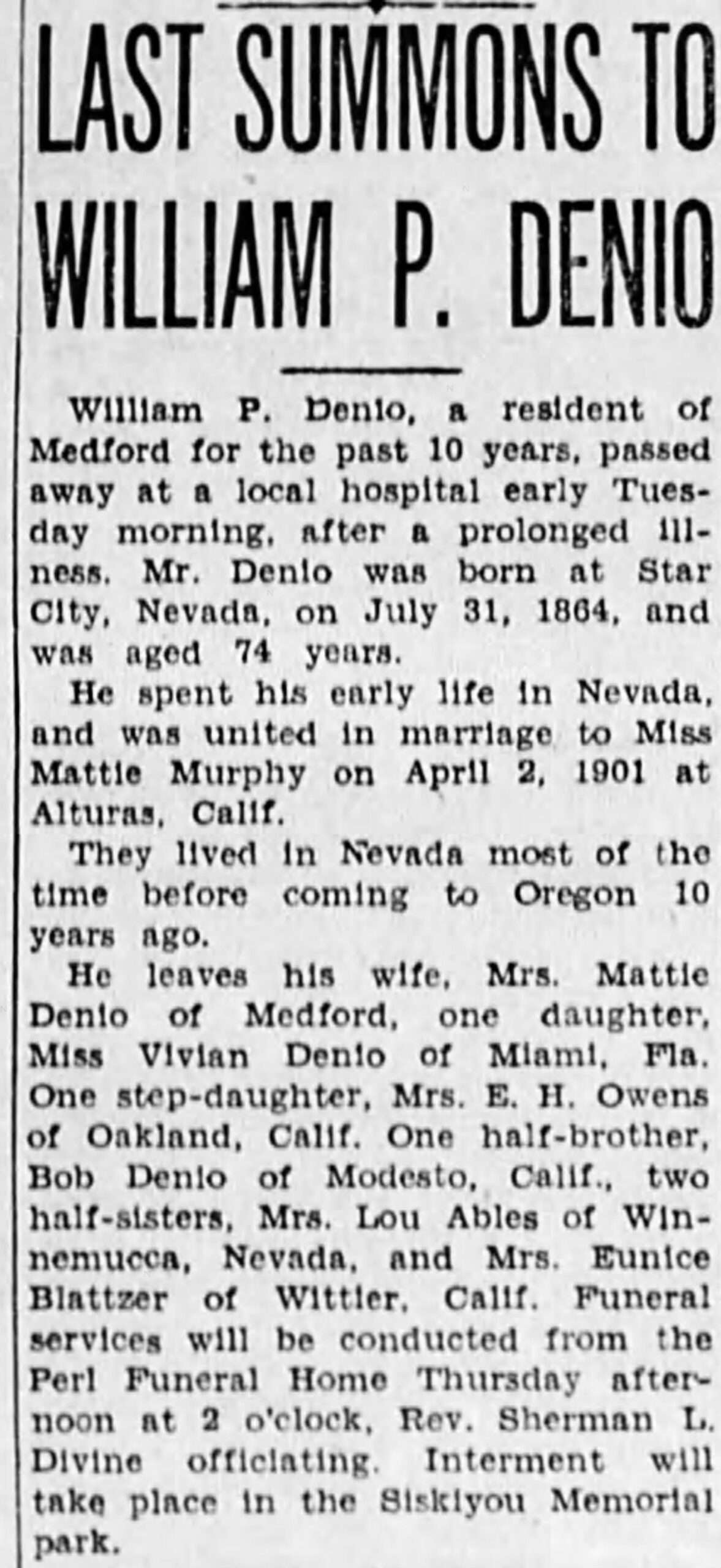

William “Billie” Denio was born to Aaron Denio and Mary Christeanna Downing on July 31 31, 1864, in Star City, north of Unionville. He had one sister and three half-siblings from his father. His brother James was killed in 1879 while riding a “vicious mule.”

Denio married Bessie McGhee on September 24, 1895. Tragically, she died at Cane Springs on September 15, 1896, at age 22. She had a 6-week-old infant daughter: the newspaper reported she gave her life for her daughter Vivian.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress)

In 1901, Denio married Mattie Murphy in Alturas, California. The couple would spend most of their lives in Nevada.

William “Billie” Denio homesteaded in this remote location, 50 miles north of Gerlach. Their home had three rooms. They had two outbuildings, one for overnight guests and the other for storage. The Denios were known as hospitable and stored supplies for sheepherders.

In 1922, Mattie Denio patented their homestead, including 320 acres. In 1924, the couple sold Denio Camp to George R. Parman and his wife Jessie from Eagleville. The Parmans did not live at the ranch full-time but purchased an apartment house in Reno. Sadly, fourteen years after purchasing Denio Camp, Jessie was mortally injured while decorating their apartment when rags covered in paint and turpentine ignited. George survived until 1951.

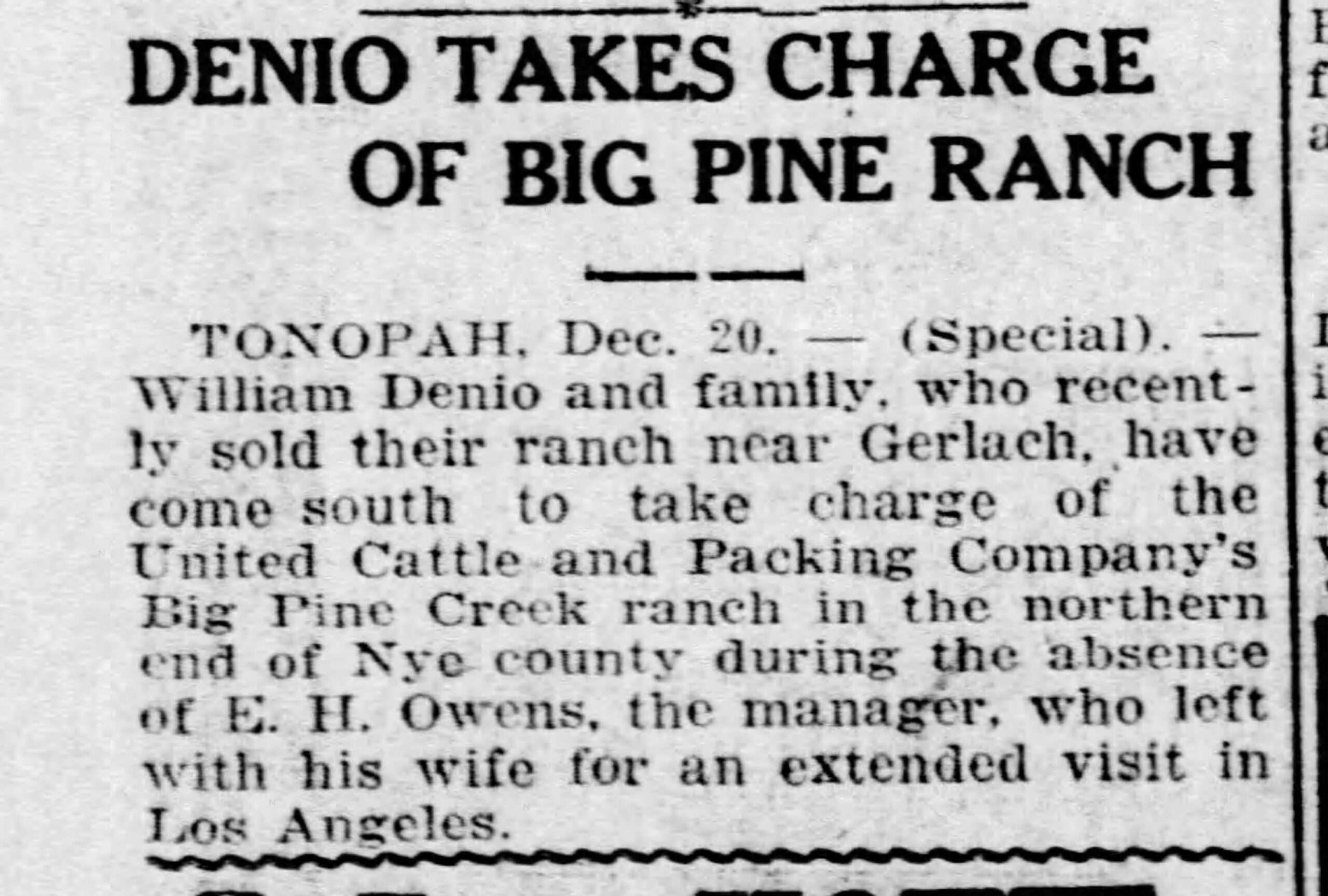

The Denios moved to Big Pine Ranch to manage the United Cattle and Packing Company’s Big Pine Creek Ranch in Nye County.

The Denios moved to Medford, Oregon sometime around 1928. William died in 1938, leaving behind his wife Mattie, daughter Vivian Denio, step-daughter E.H. Owens, half-brother Bob Denio and two half-sisters.

Medford, Oregon September 28, 1938

(Photo credit: Find a grave)

“Shoshone Mike”

With the arrival of white emigrants and settlers in southeast Idaho, conflict arose with the Shoshone and Bannock tribes. In 1868, Chief Pocatello agreed to move to the Fort Hall Reservation along the Snake River. The government agreed to provide $5000 annually of goods and supplies. Supplies were often delayed or spoiled, leading to suffering from hunger, disease and death.

(As an aside, I attended ISU and my favorite spot to study was at the Fort Hall Replica)

Ondongarte, known as Mike Daggett, lived at the Fort Hall. Alternate names include Salmon River Mike, Indian Mike, and Rock Creek Mike.

(Photo credit: Archival Idaho Photo Collection)

Daggett left the reservation with his wife; two sons, Charlie and Gnat; two daughters, Snake and Toad; two adolescent males and four children. They lived a nomadic life in Nevada. The men worked for ranchers in Elko. They were hard workers but isolated themselves from others.

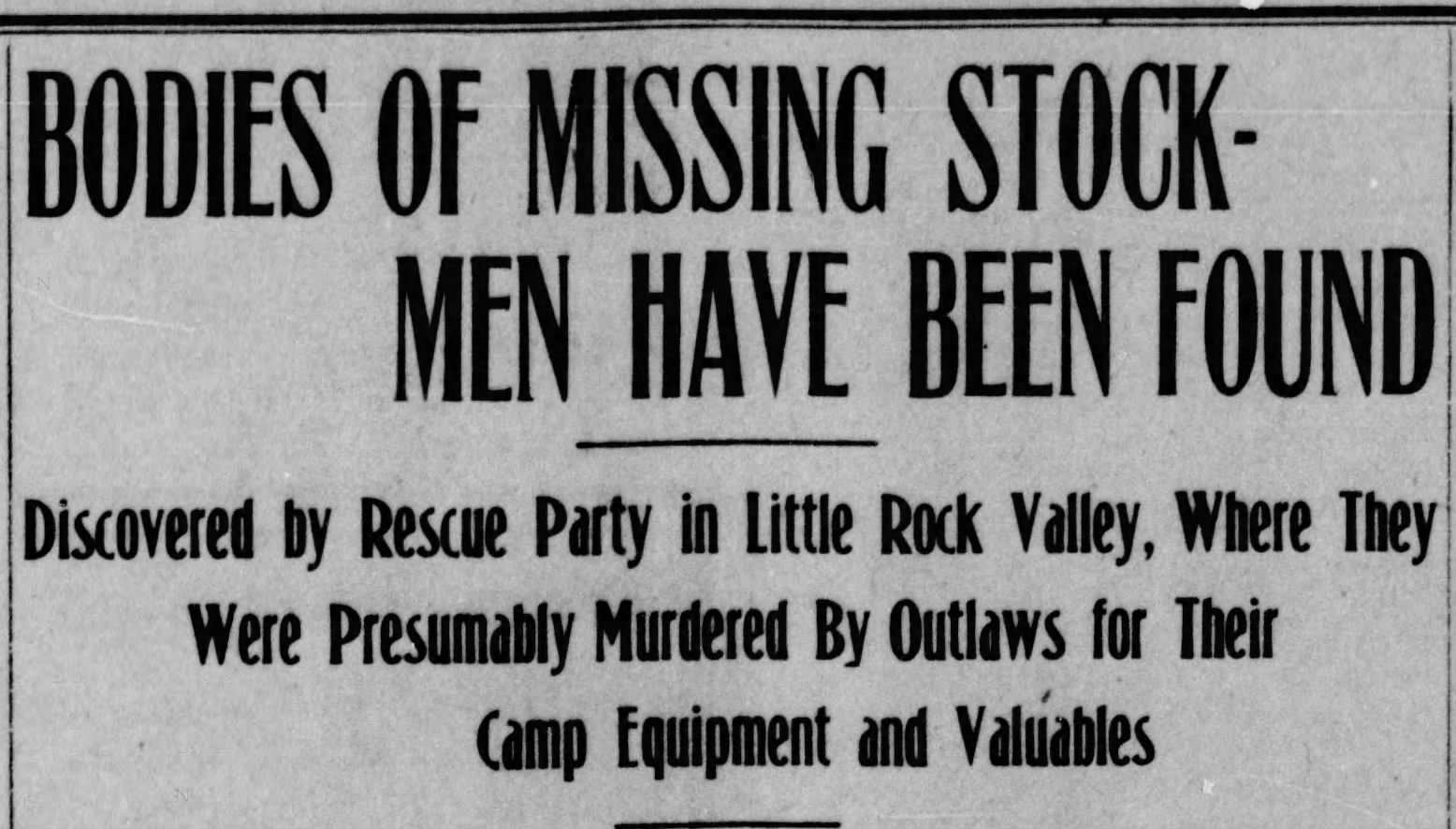

(Silver State, April 27, 1911)

In 1910, Frank Dopp and a group were out gathering cattle. A fight with the Daggetts ensued, ending in the death of Daggett’s son Dugan. In retaliation, Daggett and his group killed Dopp. Burying his body, they fled to Oroville, California. Doop’s remains were discovered two months later and reinterred at Margaret Settles ranch outside of Twin Falls, Idaho.

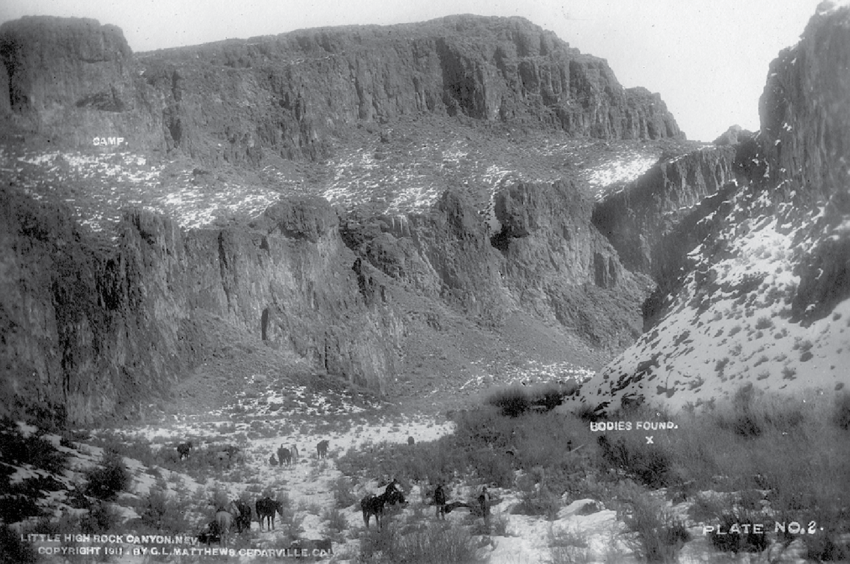

In the heavy winter of 1911, Daggett’s band settled in Little High Rock Canyon, five miles from Denio Camp. To survive, they stole a rancher’s cattle and hung them from the trees. Reportedly, a few days before the cattle theft, the Daggetts robbed and killed an unnamed man from China and buried his body.

The Four Stockmen

Sheepheader Bert Indiano witnessed the Daggetts rustling cattle. He has driven away from the canyon and ran into rancher Harry Cambron and sheepmen Peter Erramouspe and John Laxague.

(Photo Credit: Library of Congress)

Indiano, Cambron, Erramouspe and Laxague headed out to search for their stock. Their last stop was at Denio Camp on January 18, 1911, where they spent the night. Billie and Mattie were the last to see the men alive.

On January 19, the ranchers rode into Little High Rock Canyon, where Mike and his family camped. Thinking the men were seeking vengeance for the rustled cattle, the Daggetts ambushed and killed the ranchers. Following their deaths, their bodies were mutilated, and their clothing was stolen. Mike’s band fled east.

Search Party

Families and coworkers became concerned when the four men didn’t return as expected. A herder headed towards Eagleville to investigate. Stopping at Denio Camp, he learned the group headed to Little High Rock Canyon. Denio penned letters to the wives on what he knew of the situation. In Eagleville, some thought the men were buried in a snowslide, but many feared Daggett’s band killed them.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress)

(Historic photo credit: Library of Congress)

Despite the snowstorm, a search party formed at the Eagleville church and headed out. They stopped at Denio Camp, gathering information, and headed toward the canyon. The pre-arranged signal for the search party was that if someone found the missing men, he was to fire three shots. Warren Fruits stumbled on the remains, lying in a creek side by side. Startled by the discovery, he fired five shots. Thinking he was under attack, the others came running, ready to join the battle.

Winnemucca, Nevada · Saturday, February 11, 1911

One search party member headed to Eagleville with the terrible news, and messages were sent to surrounding law enforcement. The deceased were taken to Denio Camp, where the physician held an inquest, finding the men had all been shot through the head to ensure they were dead. Their remains were returned to Eagleville, where they were interred.

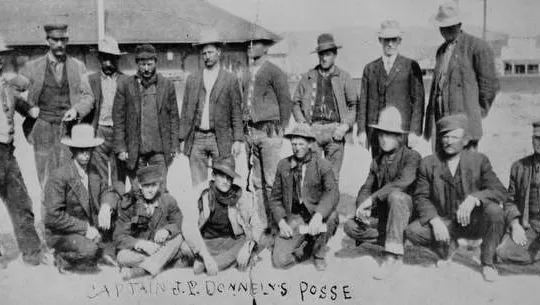

Posse

Multiple posses formed, including one under the command of Captain J.P. Donnelley. A bounty was placed on Daggett’s band, paid to the person who arrested or killed them. Fifty-five men gathered at Denio Camp. The Denios kept the men well-fed and tried to make them as comfortable as possible. The men helped out by washing dishes and cutting sagebrushes for fires to stay warm.

Famed Sheriff Lamb and Skinny Pascal, a Paiute tracker, joined the group at Lay’s ranch. Donnelley’s posse followed Daggett’s trail 200 miles across the Black Rock Desert, to Quinn River, around the Santa Rosa Mountains and east to the Little Humboldt River.

Reno, Nevada · Sunday, January 26, 1913

On February 26, 1911, the posse finally caught up with Daggett’s band at Kelly Creek, outside Golconda, northeast of Winnemucca. A battle ensued, resulting in the death of Mike Daggett and all members of his band, except Snake, a teenage girl, a young girl, a boy, and a baby in a papoose.

(Photo credit: Nevada Historical Society)

Daggett’s band was buried in a mass grave at Golconda. A farmer later donated the remains to the Smithsonian Institute. Finally, they were repatriated to the Fort Hall Idaho Shoshone-Bannock Tribe.

The police took the surviving children to the Washoe County Jail, where they remained for several months until they moved to the Stewart Indian School. By 1913, the three older children died of tuberculosis.

Only Mary Jo, Mike Daggett’s granddaughter, survived. Evan Estep, the Fort Hall reservation superintendent, and his wife, Orrell Marietta “Rita,” adopted Mary Jo. While attending Central Washington University, Mary Jo became a school music teacher. She did not learn the details of the battle until 1975.

One member of the posse, Ed Hogle, died in the shootout. Captain Donnelly swore him in as a law enforcement officer the morning they found Daggett. His remains were interred at Anderson, in Shasta County, California. His mother and fiancée survived him.

Conclusion

This article is about the abandoned Denio Camp, the couple who created the beautiful ranch, and its role in Nevada History.

As is sadly true, history is often marked by tragedy. We can study documents, newspaper accounts and interviews concerning the deaths of the four ranchers and the Daggetts’ band. In-depth information about both tragic events is inconsistent and often biased.

For more information and photos, please refer to the reference list.

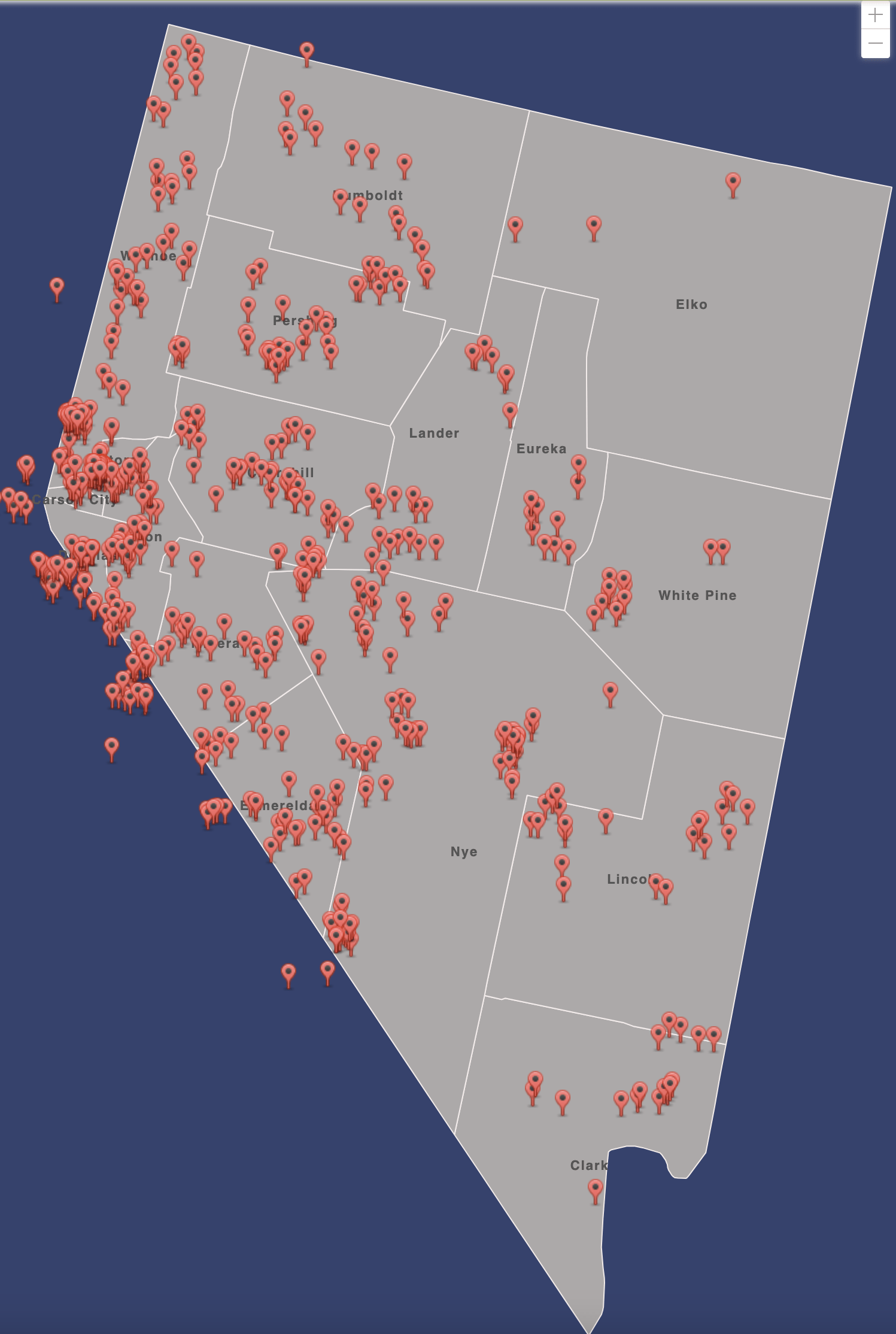

WANT MORE GHOST TOWNS?

For information on more than five hundred ghost towns in Nevada & California, visit the Nevada Ghost Towns Map or a list of Nevada ghost towns.

References

- Blackrock Desert: Denio Camp Spring

- The Eureka Sentinel Mar 4, 1911

- Howard Hickson Histoies: The Last Indian Uprising?

- The Lassen Advocate Feb 10, 1911

- The Lassen Advocate Feb 24, 1911

- Lassen Advocate Oct 22, 1982

- Library of Congress: Camp Denio

- The Modoc County Record Jul 11, 1963

- Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, Winter 1972. The Last Indian Uprising in the United States

- Nevada State Journal Jan 26, 1913

- Nevada State Journal Oct 25, 1959

- Reno Gazette-Journal Dec 07, 1910

- Reno Gazette-Journal Feb 8, 1911

- Reno Gazette-Journal Aug 6, 1921

- Reno Gazette-Journal Apr 23, 1938

- Reno Gazette-Journal Dec 17, 1951

- Robertson, Dorothy. Northwestern Nevada’s historic little high rock country

- The Silver State Aug 28, 1895

- The Silver State Sep 25, 1895

- The Silver State Sep 15, 1896

- The Silver State Feb 11, 1911

- The Silver State April 27, 1911

- Teaching American History: Survivor returns to site of last Indian massacre

- The Times-News July 21, 1910

- Yerington Times Mar 4, 1911

- Washoe Document # 3226October 17, 1924

Ken Baldwin says

Very interesting! I’d never heard about the massacre. I do some fly fishing in northern Washoe County and will try to make a side trip here one day. Thank you!

Tami says

Glad you learned something new.

I will dive more into it this summer. I’ll be up in High Rock Canyon.

Bob Deckwa says

I have a book on the battle. It states that it was in 1935. It took place a the juncture of Rabbit Creek and Kelly Creek. The location is on a ranch on the road to Tuscarora just past the turn to Golconda Mine.

Tami says

Interesting, I found a ton of newspaper articles and they are all from 1911.

I’d like to visit the site when I’m out that way. I have driven that road but didn’t know about the battle at the time. Hopefully On-X can help me contact the owners.

Anonymous says

Great article – thank you!

Chuck Young says

Great research thank you… always look forward to seeing one of your post pop up in my inbox.

Tami says

Thank you, so glad you enjoy the articles.

Bill Curtiss says

Great article love learning about areas I use to go to last time I was in Denio there were still people living there a gas station bar and store

Tami says

Glad you enjoyed it. There are still some people living in Denio, I looked for a family connection between the Denios but it wasn’t a close one.

Bill Johnson says

The stockmen were killed at Little High Rock Canyon, not High Rock further north. I’ve been there twice, and it’s a good 1+ mile walk-in. Using the 1911 photos, it’s easy to locate the Indian camp and the site where the bodies were found.

You’ve written another great account of a little-known event in Nevada history, thank you!

Tami says

Sorry, “Little” got dropped off one of the mentions of the canyon. It is updated now.

I’ll be camping up there this summer and plan on taking the photos to find the exact sites and recreate the photos.

Guy Hacker says

Great article so informative and interesting . Keep up the good work. My wife and I love exploring Nevada’s ghost towns and mines.

Tami says

Thanks and glad you enjoyed the research and story.