Bodie is a well-visited and documented ghost town. Sadly, some parts of its story are often forgotten. The Chinese played a critical role in the history of Bodie and the Eastern Sierra. Not allowed to work in the mines, they worked as laborers. It was their efforts that kept Bodie warm in the winter, supplied them with wood for cooking, and kept the mills operating.

Multiple wood camps formed outside Bodie, including China Camp. Little remains to mark their passage, except for a single grave with a faintly carved cross bearing the inscription “Chinese Man 1898.” A mystery surrounds the grave at China Camp. Is it real?

Chinese in the Eastern Sierra

The Chinese have a long history in the eastern Sierra. The earliest recorded instance is in 1856, when immigrants dug ditches along the Carson River. In 1860, twenty-one Chinese men resided in the Western Great Basin; by 1880, the population had grown to 5,416, comprising 5,102 males and 314 females. Many Chinese workers came from Guangzhou, bringing a culture that sometimes clashed with that of European settlers.

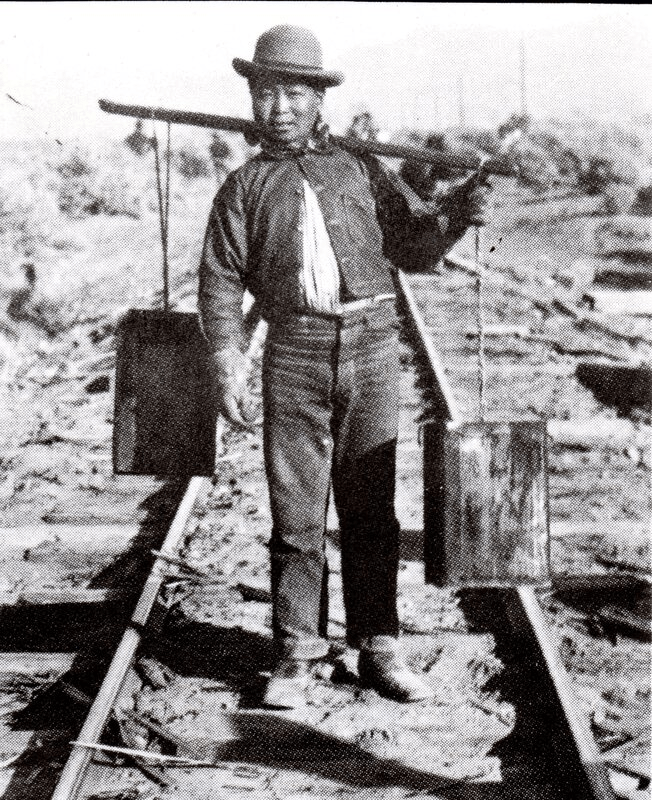

(Photo credit: Around Carson)

Miners’ unions prohibited the Chinese from working underground, so they worked as laborers, woodcutters, laundrymen, and servants. Chinese faced more discrimination than any other minority group. In some towns, the Chinese built underground cities and stayed out of sight during the night to avoid persecution.

(Photo credit: Northeastern Nevada Historical Society)

Chinese laborers comprised 90% of the Central Pacific Railroad’s builders. The workers leveled land, built bridges, and laid tracks. Workers lived in tent towns and were paid from a train car, with other cars providing gambling and female companionship.

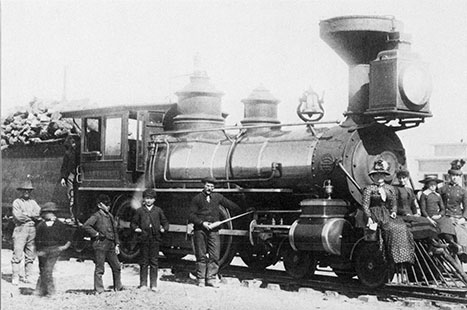

(Photo credit: Laws Railroad Museum)

After the completion of the transcontinental railroad, many workers transitioned to smaller, narrow-gauge lines. The narrow gauge Carson & Colorado Railway ran from Moundhouse, Nevada, to Keeler, California, south of Cerro Gordo Mines. Construction began on May 31, 1880, and the first train arrived at Keeler on August 1, 1883. The route ran on the east side of Walker Lake to Hawthorne.

Hawthorne had a good-sized Chinatown. Most of the men were single, or their wives remained in China. Chinatown had its own cemetery, possibly with hundreds of graves. Unfortunately, details were lost to time; however, human-remains detection dogs identified several graves.

After the railroad was completed, many Chinese laborers built the wagon road from Hawthorne to Aurora and Bodie. Some started wood camps near Aurora, Bodie, and Masonic.

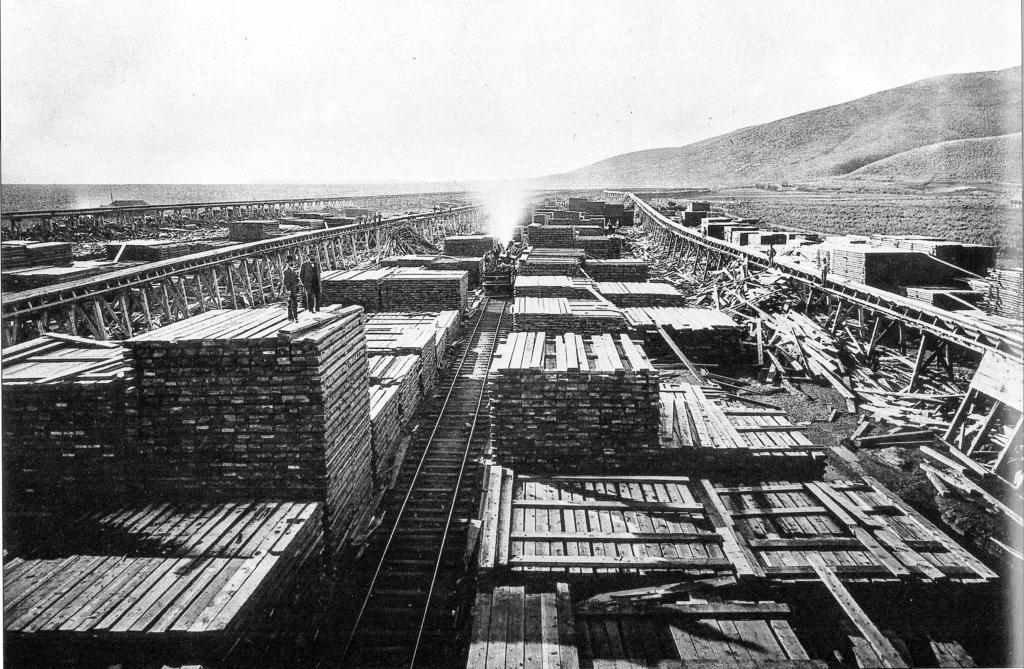

Bodie’s insatiable need for wood

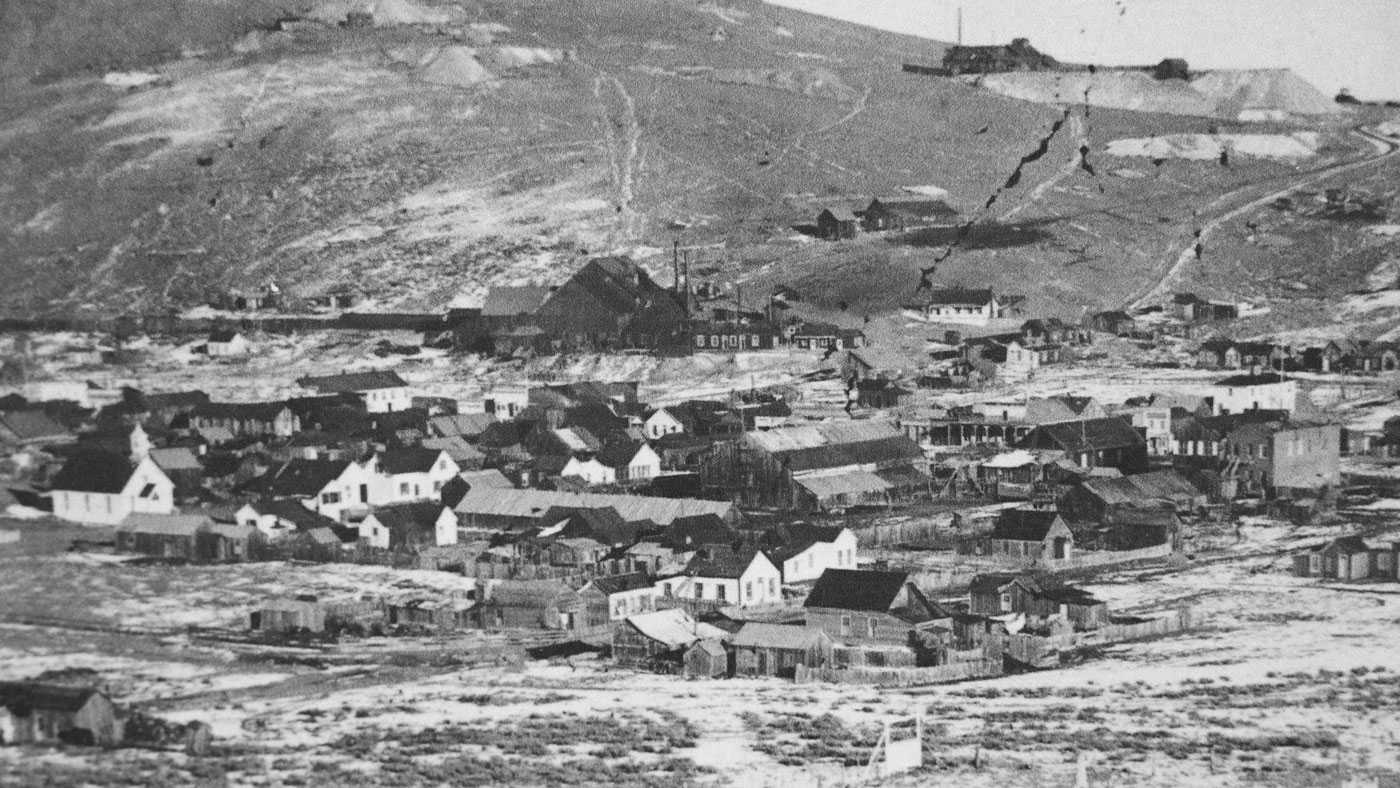

By the late 1800s, 20,000 people lived in Bodie and Aurora. They may have been rich in gold, but they lacked other essential resources, including lumber. Carson City’s mills were expected to fill only two-thirds of the lumber orders.

(Photo credit: WNHPC)

(Photo credit: UNLV Special Collections)

Chinese settled in Aurora in the 1860s and in Bodie a decade later. In Bodie, they settled northwest of Main and King Streets. At the peak, several hundred Chinese lived in Bodie. Chinatown included stores, temples, homes, boarding houses, saloons, and opium dens.

(Photo credit: You know you love Bodie)

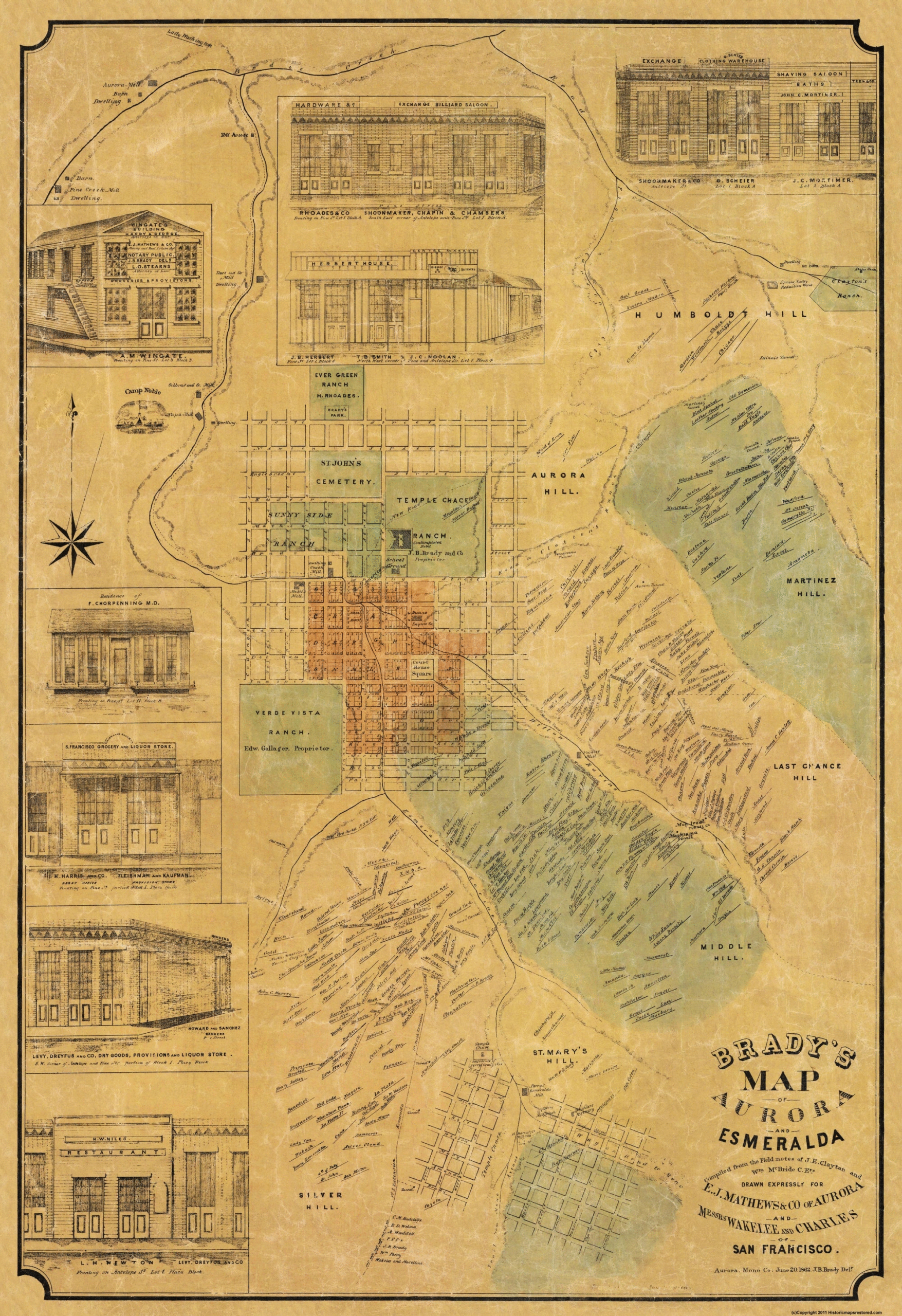

An ordinance passed in 1864 prohibited Chinese people from living within Aurora’s town limits. Aurora’s Chinatown was on the outskirts of town, centered around Spring and Roman Streets. The area became known as the Chinese Garden or China Gardens, as many cleared land to raise produce.

Unlike many Western towns, the Chinese did not experience organized violence in Bodie and Aurora. Tong fighting accounted for most of the violence in Chinatown. Nine violent deaths were associated with the Chinese or Chinatown; most revolved around the opium dens. Five whites died in Chinatown, two were shot by white men, two overdosed on opium, and one woman committed suicide. Deaths of Chinese included being shot or stabbed by another Chinese, beaten to death by an unknown assailant, and one man from Mexico shot by a man from China. However, the Chinese were disproportionately involved in theft, selling liquor to Indians, and violence against women.

Woodcutters

The U.S. Census records 35 Chinese workers employed at Bodie as woodcutters. Sam Chung employed Chinese laborers to bring wood to Bodie as early as 1878. One woodcutter stored 300 cords at his Bodie lot, while another had more than 1,000 ready for delivery. In 1881, woodcutters harvested an estimated 20,000 cords of wood.

Prices of firewood varied seasonally and by location. On average, firewood costs $10 per cord in Bodie, whereas in Bridgeport it was only half that price. Over winter, the price could double and even triple during heavy storms.

The Chinese faced many challenges in woodcutting. Mules became injured or died from weather, transportation accidents, and fighting over woodlots.

The Chinese often banded together to help one another. A snowstorm trapped Sam Hoo on the road to Bridgeport. A search party unburied Sam and his mules, bringing them to town. In another instance, they banded together to repack loads after the mules became spooked.

China Camp

At least eleven woodcutting camps existed north of Bodie and Aurora. There are likely many more in the vicinity of Bodie. USGS maps from 1884 to 1901 indicated that Chinese men held twenty-four taxed, timbered parcels as wood lots. At least nine different men owned the parcels over the years.

Multiple people excavated or surveyed the camps, including amateur archaeologist Robert Morrill in the 1960s and 1970s, a USFS district employee and later volunteer and author, Clifford Shaw, and Emily Dale, who conducted surveys between 2011 and 2014 as part of her doctoral dissertation.

The Chinese woodcutter camps vary in size and complexity. They include dugouts, collapsed cabins and foundations, rock walls, and fences. When excavated, researchers found bottles, tools, hardware, and saws. Also found were remnants of everyday life, including pottery, bottles, cans, coins, clothing accessories, and game pieces. At most sites, excavators discovered opium containers.

China Camp was active from 1870 through the 1920s. In the various surveys. Because of its more accessible location, China Camp has been damaged and looted to a greater extent than the other camps.

China Camp includes one to two dogouts, rock-lined walls, and debris. Surveys identified hardware, ammunition, porcelain, and Chinese coins dating from 1722 to 1736. The site also included parts of a harness and a sleigh, indicating that horses or mules were used.

The site also includes a collapsed cabin. Round-headed nails hold boards together, dating the cabin to the 1900s.

China Camp Grave

The most notable feature of China Camp is a lone grave with a wooden marker. If you look closely, you can see it is engraved “Chinese Man 1898.”

In reviewing the extensive survey reports, the grave at China Camp was omitted. Why is this not listed in the archaeological surveys? A former USFS employee believed the grave could have been dismissed as a hoax because it is located at a modern campsite. But people have camped at well-marked cemeteries, including nearby Pine Grove, so this might not be an exclusion criterion.

Due to cultural beliefs, many Chinese desired the return of their remains to their homeland. While this happened, there are many graves of Chinese, and even an entire Chinese cemetery in nearby Hawthorne.

There are no historical photographs of the grave or marker to date it.

Is the grave that of a Chinese woodcutter? It could be. But, it might not be. It would be interesting to use human-remains detection dogs and see whether they alert. Barring further research and investigation, it will remain another Nevada mystery.

WANT MORE GHOST TOWNS?

For information on more than five hundred ghost towns in Nevada & California, visit the Nevada Ghost Towns Map or a list of Nevada ghost towns.

Learn about how to visit ghost towns safely.

References

- Chung, Sue Fawn, Nevada State Museum. The Chinese in Nevada. Acadia Press, 2011.

- Dale, Emily. Give Me a Y-Beam: Architecture and Agency at Rural Chinese Woodchopping Camps, Mineral County, Nevada (2015)

- Dale, Emily. Chinese Agency in the Era of the Chinese Question: Historical Archaeology of Woodcutting Communities in Nevada, 1861-1920

- Dale, Emily. Households of the Overseas Chinese in Aurora, Nevada (2013

- Dale, Emily. There’s a Hole in My Bucket! (But I Put it There on Purpose): Modified Can Use at Rural Woodcutting Camps in Mineral County, Nevada

- McGrath, Roger D. Gunfighters, Highwaymen and Villains: Violence on the Frontier. University of California Press. 1984.

- Apollonia Morrill: Charcoal Camp, Sweetwater Mountains, Nevada

- National Park Service: Bodie Historic District

- Nevada State Museum: FUELING THE BOOM: CHINESE WOODCUTTERS IN THE GREAT BASIN 1870-1920

- Shaw, Flifford Alpheus. Aurora, Nevada 1860-1960: Mining Camp, frontier city, ghost town. 2018

- Silver, Sue. Mineral County, Nevada. Volume 4: Progress and People. Museum Associates of Mineral County, 2011.

terry says

good to see you are up to putting out articles again.

Tami says

So happy to be getting back to what I love!

Bob Hansen says

Thank you Tami!

Glad to have you back 🙂

Tami says

Thank you!