Heading to Bodie or Aurora? Why take the modern route when you can follow the old stage road from Genoa to Aurora or Bodie? Even if you are driving Highway 395, you can still follow a portion of the old route.

Genoa and Carson City were the primary supply and service centers for the eastern Sierra. Toll roads connected travelers from the southern mines to Genoa and Carson City and, eventually, the transcontinental railroad to San Francisco. The route is filled with stories of Highwaymen, murder, lost treasure and not just one, but two axe-wielding maniacs!

The stations are in order from Genoa to Bodie. Always check road conditions. The Boyd Toll route follows paved roads until it departs Sweetwater; then it is a graded road to Fletcher. Past the turnoff to Aurora, the road through Bodie Canyon is notorious for washouts. This section is only recommended for experienced drivers with high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicles; even then, the canyon frequently becomes impassable due to washouts. Olds’ Toll Road is four-wheel drive only.

Each site has a brief description. Blue headings link to articles with more information.

Genoa

Situated at the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, Genoa became an important waypoint for the ’49ers. By 1850, Mormons had built a stockade and corrals and opened a trading post called Mormon Station. The station sold food, clothing, tobacco and other supplies to those joining the gold rush. John Reese arrived with twelve wagons, supplies and stock in 1851 and created the settlement in what would become Nevada.

Genoa became a major supply center for the eastern Sierra. It connected travelers from Bodie and Aurora to Carson City and, eventually, the transcontinental railroad in Truckee Meadows.

Toll Roads & Stations

During early mining booms, roads were difficult and time-consuming to construct. The Nevada Territory lacked the resources to build and maintain the infrastructure. Between 1861 and 1864, Nevada awarded toll road franchises to individuals or groups who bid to construct roads. In return for their investment and continued maintenance, travelers compensated the owners with tolls. Stations had a gate or house where owners collected tolls. They often provided food and shelter for weary travelers.

After a rich silver and gold ore strike in 1860 on the border of Nevada and California, travelers needed a road to connect Genoa to the eastern Sierra mines around Mono Lake.

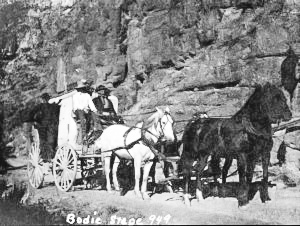

(Photo credit: Bodie Foundation)

Despite close ties and heavy traffic between Bodie and San Francisco, travel between the cities was difficult. The fastest route headed from Bodie was via a stagecoach to Aurora, followed by another stagecoach to Carson City, and then boarding the Virginia & Truckee Railroad to Reno, before connecting to the Central Pacific Railway to San Francisco. A traveler could count on a several-day trip, with meals and accommodations ranging from opulent to horrid.

Road Agents

Stagecoach robberies were common on many routes, including Blanchard’s Toll Road in Bodie Canyon. Sharp curves, narrow passages, steep cliffs and isolation were ideal for a ne’er-do-well looking to enhance his income. Some say that robberies occurred so frequently that horse teams would halt themselves in the canyon to await the arrival of highwaymen.

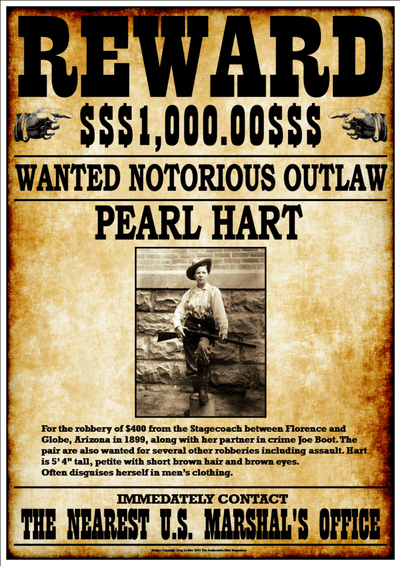

Stories differ on how stagecoach robbers behaved. Some robbers were polite to passengers, neither touching them nor their belongings, as selling stolen property in the sparsely populated West was risky and rewards were frequently posted. No one wanted his likeness on a wanted poster.

(Photo credit: Andromeda Print Emporium)

During other hold-ups, once the cash box was relieved, robbers demanded at gunpoint that passengers place all their valuables in the bandit’s hat. After freeing the passengers from their possessions, the highwaymen made a fast, clean getaway.

(Photo credit: Legends of America)

Both versions of the bandits are probably true. The Hollywood movie Desperado and the Victorian gentleman thief likely coexisted. One agreeable highwayman posed for a photograph during a robbery, taking an 1880s-style selfie with his victims!

Olds’ Old Toll Road (4-wheel drive only)

David Olds built the original road to connect to the southern mines. His trail headed south from Genoa, following the Emigrant route along the foothills. Stations included Van Sickle, Mottsville, Sheridan, and Fairview.

From Fairview, the route departed the Carson River Emigrant Route. It headed to Dutch Valley and C.P. Young’s ranch. At Young’s Crossing on the East Fork of the Walker River, Olds had a ferry franchise to transport wagons across the river during high water. The road proceeded to Douds Station, then Double Springs, where Olds Road ended.

Doud’s Station

Edward Doud sold his ranch in Alpine County, California, in 1873. He moved to a beautiful spring along Olds Toll Road, which became known as Doud’s Station. Teamsters enjoyed fresh water from the perennial springs. Doud lived in a small cabin, only 10′ x 12′. The field was fenced with stacked rock walls.

In 1882, a man searching for work discovered Doud lying on the floor of the cabin, covered with a bloody sheet. An axe lay nearby. The attack was so brutal that Doud was hacked into pieces, making identification difficult. Citizens of Genoa were horrified, but no assailant was brought to trial, despite a reward.

Boyd Toll Road

On December 19, 1861, William Boyd received a toll road franchise to connect Genoa with Wheeler’s Station (Twelve Mile) in southern Carson Valley. Departing Genoa, the route headed to Cradlebaugh Road, which ran from Carson City to Desert Station. It then proceeded four miles to Wheeler’s Station.

In 1863, a telegraph ran between Placerville, California, to Genoa and, later, to Aurora. The line flanked Boyd’s Toll Road, with many renaming it Telegraph Road. Douglas County purchased the road from Henry Van Sickle and Lawrence Giman in 1876 for $2,650.

Boyd’s Toll Road replaced Olds and became the primary route to Esmerelda. Today, you can travel most of the road to Aurora and Bodie.

Twelve Mile House

In 1859, Thomas Wheeler built a stage stop in South Carson Valley. Wheeler’s Station was situated at the south end of Carson Valley, where the road begins to climb into the hills. This location is a critical crossroads. The road south continued towards Aurora, Bodie and Goldfield. To the west, it continued to Fairview and Woodfords, where it joined the Carson River Route of the emigrant trail. The road north leads to Nevada’s oldest settlement, Genoa, Carson City, and Virginia City.

The station changed hands many times, including with Jack Teasdale. Many mile houses were named after their location on the road or in relation to other stations. Twelve Mile House is 12 miles from the prior stage stop in Genoa and 12 miles from the Cradlebaugh Bridge, where the road crosses the Carson River.

In the early 1870s, Sheriff H.C. Crippen and his wife took over the station. Crippen constructed a two-story hotel; his wife was known for her delectable food. Twelve Mile House became a social hub, hosting numerous dances and parties. Sadly, Crippen committed suicide in 1880.

Fredrick “Fritz” and Margaret Springmeyer assumed the station in 1890. It remained in the family until the U.S. Government purchased it in 1936 and became part of the Washoe Indian Reservation.

Jake’s Place/Rodenbaugh

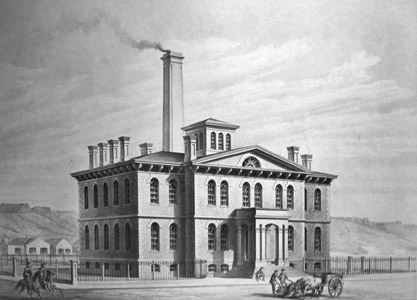

Jacob ‘Jake’ Rodenbaugh emigrated west to California with the Gold Rush. Not having luck as a prospector, he settled in Carson Valley in 1860. Rodenbaugh had kilns in the Pine Nut Mountains and provided charcoal to the Carson City Mint and mines in Virginia City. Later, his kilns fueled the mills of Aurora and Bodie.

(Photo credit: US Treasury)

With increased traffic to Esmerelda, Jack built a station known as “Jake’s Place.” The location was ideal, right before the steep climb up Jake’s Hill. Some say Jake’s was the most popular stop along the route. Jake died in 1913 at age 71. His wife, Delilah, managed the station until 1916.

Louis Ruhenstroth purchased the station and built the beautiful two-story brick house. The station operated for only one year.

Carter’s Station

While only four miles past Jake’s Place, Carter’s Station was a welcome break from the steep climb. John and Minerva Carter moved to Carson Valley in 1864 with their daughter Delilah, who later married Jake Rodenbaugh. The Carters opened a station and a mining supply store. The Carters added their son Charles in 1867, and he later attended school at Twelve Mile House.

John continued to prospect and found ore gold. He worked the claim with little success. Minerva ran the station for a few months after John’s death in 1888. She moved with her son Charles and his wife to Smith Valley.

Mammoth Lodge

Daniel Hawkins established this station in 1861. Mammoth Lodge served as a polling place and operated as a post office from 1863 to 1867 and again from 1868 to 1869. Mammoth Lodge was in the Eagle Mining District. Nearby was the significant first silver discovery in the Pine Nut Mountains. Mammoth Lodge was short-lived and closed with the opening of Carter’s Station.

Double Springs

Two springs lend their name to the station. Double Springs is at the juncture of Olds and Byod Toll Roads and Rissure Toll Road to the south, heading towards Esmerelda. S.D. Fairchild established the station in 1861, which included a hotel, barn, and stable.

H.W. Bagley acquired the property briefly before James Dean and his wife took over. Soon thereafter, Dean was appointed Justice of the Peace. Several years later, a wagon arrived, and the driver found Dean’s wife beaten and drowned in a bucket. The sheriff held Dean for his wife’s murder but released him for lack of evidence. Dean soon sold the station to the Spragues.

The last owner of Double Springs was James Meder. The station was abandoned by 1885.

Lost Treasure

In 1863, a lone highwayman held up the stage from Aurora to Carson City. As luck, or planning, would have it, the stage carried $17,000 in gold. The robber escaped with the treasure, but was unable to carry the weighty loot.

The law didn’t take kindly to the theft and pursued the highwayman. Catching up with their prey, they sentenced him to the Nevada State Prison in Carson City. The man kept the location of the buried treasure secret until he was on his deathbed, saying the treasure was by a cabin, half a mile north of Mountain House.

Treasure hunters searched for the gold for many years, but it was never located. (The land is now private, so no hunting without permission.)

Mountain House

Next on the stop was Mountain House, also known as Holbrook Station (different than Holbrook Junction). La Seaux operated a bare necessities station. Charles Kilgore purchased the property in 1875 and added a hotel and barn. He planted beautiful trees, creating much welcome shade.

Highway Men robbed a stage heading from Aurora toward Mountain House that fall. The bandits absconded with $225. They were arrested in Amador County several weeks later.

In 1878, a telegraph line connected Genoa and Bodie, later extending to Aurora, with an office located in Mountain House. The station changed hands several times over the years. Fire from an unattended candle burned the station in 1914, and the post office closed the following year.

Hoye Station

Walker River Station is also known as Rissue’s Bridge. It was located south of Smith Valley in beautiful Hoye Canyon. Thomas Rissue was Justice of the Peace for the Walker River precinct. From Mountain House to Wellington, he was awarded the toll franchise in 1864.

The road had a station and a bridge on the East Walker River between Antelope and Smith Valleys. Previously, Rissue’s uncle ran a ferry service at the exact location. After crossing the bridge, the road continued through the canyon to Wellington, where Rissue’s road ended and joined the Dixon Toll Road between Dayton and Aurora.

John and Mary Hoye emigrated from Ireland. After settling in Carson City, they moved to Smith Valley, where they had a small station near Artesia Lake. They relocated to north Antelope Valley and acquired the Rissue’s bridge, relocating it to their property. The section of road through what became known as Hoye Canyon was the most significant challenge between Geno and Aurora. Washouts, drownings and highwaymen all created life-threatening challenges. The Hoyes lost their only son in 1871 to “child’s disease” (possibly epilepsy). In 1881, the Hoyes moved their station several miles to the junction of Jack Wright Pass.

(Photo credit: Find a Grave)

Wellington

In 1861, Jack Wright and Len Hamilton built a bridge across the West Fork of the Walker River in southern Smith Valley. The site was located at a crossroads between the Dayton-Hinds Toll Road and the Rissue Toll Road to the south. Wellington Station became a critical station on the route to the southern mines.

A post office opened in 1865, and Wellington became the trading and community center of Smith Valley. Daniel Wellington purchased the station in 1893 and built a beautiful house, a hotel, and a stable.

John and Mary Hoye built a beautiful home in 1878. The large house had four fireplaces, a screened-in porch, a barn, a blacksmith shop, gardens and an orchard. They rented beds to travelers in the attack. Mary was known for setting a beautiful table with delectable meals.

Wells Fargo office 1872 to 1890.

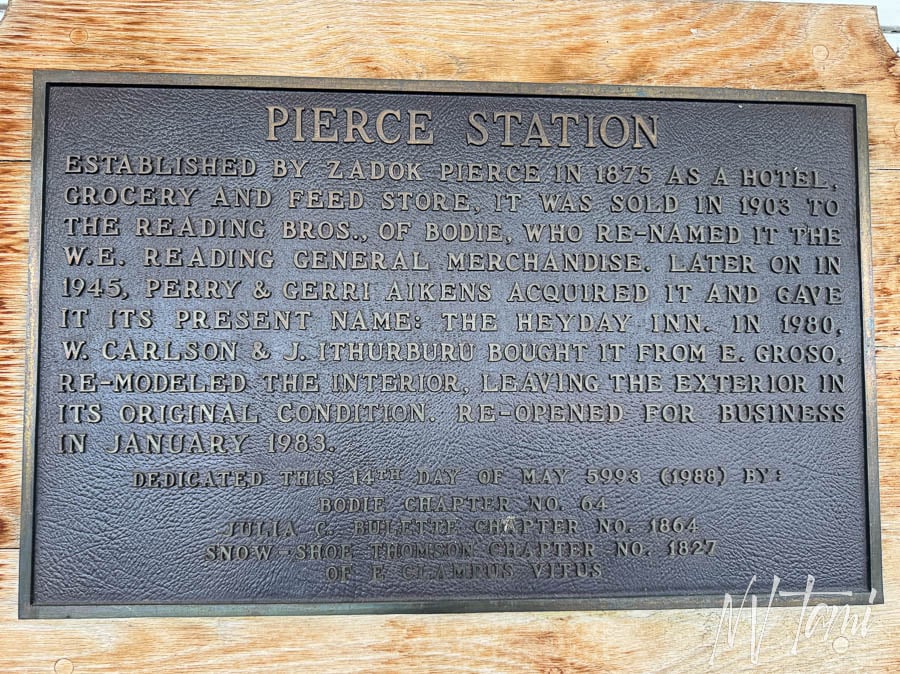

Pierce Station

Zadok Pierce opened a station in 1875, only a few miles from Wellington Station. The station had a hotel, supplies, and a feed store. Bodie resident W.E. Reading purchased the store in 1903, renaming it W.E. Reading General Merchandise.

In 1945, Perry & Gerri Aikens assumed ownership, naming the restaurant the Heyday Inn. It remains a popular saloon and restaurant known for its wonderful Basque dinners and picon drinks.

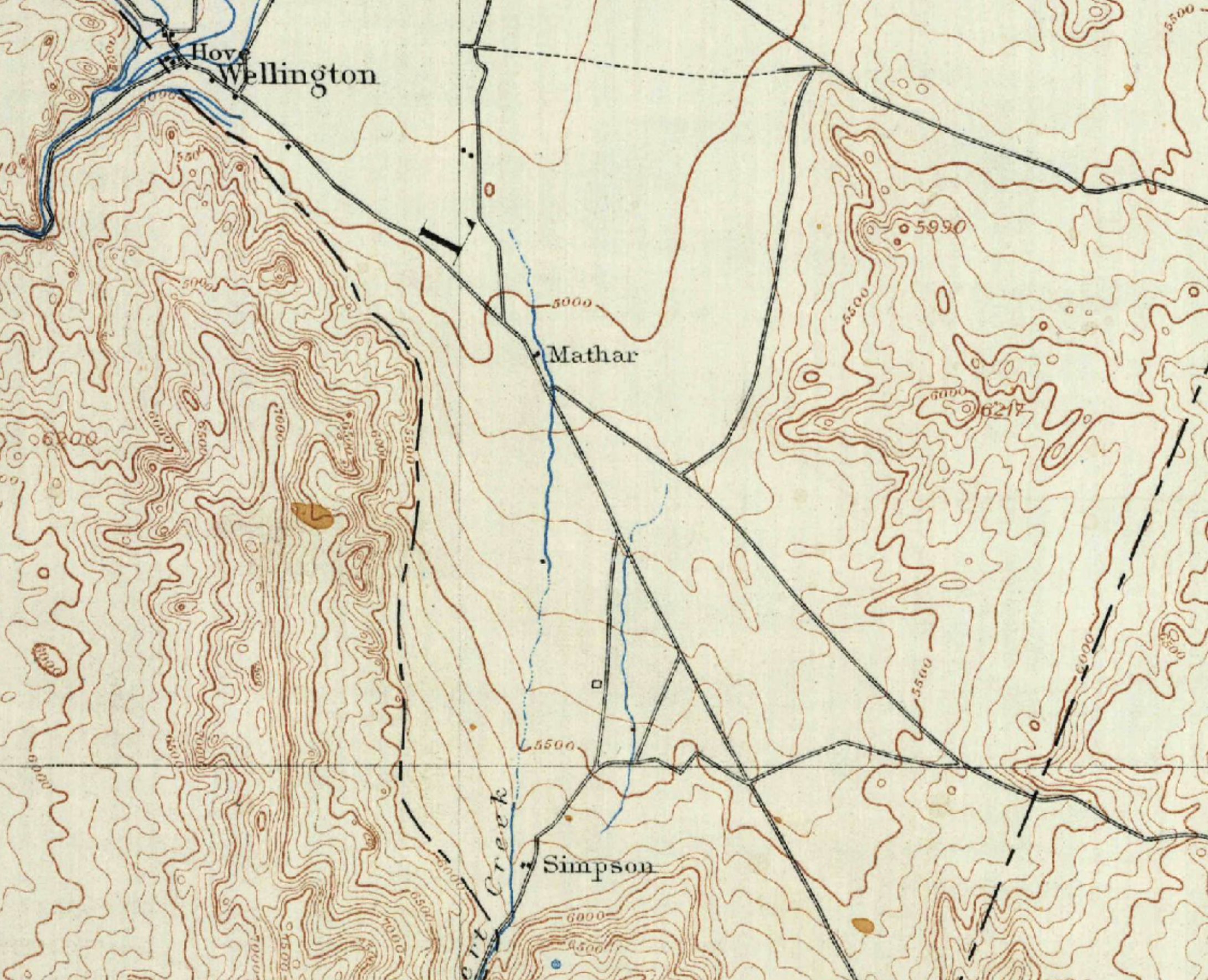

Desert Station/Mathar

J.B. Lobdell settled a ranch at the southern tip of Smith Valley in the early 1860s. Hank Mathar purchased the ranch in 1868. He built a ranch house between 1880 and 1883, which doubled as a stage station. In 1933, Ambro and Belle Rosachi assumed the ranch and expanded their properties.

Sulfur

With the rush to Esmerelda, travelers camped at Sulfur Springs. Despite being named for the sulfur deposits, newspapers described the water as sweet.

Louis and Dorothy Wedertz settled at Sulfur Springs. The couple’s son, Charles Edward, was born at the station in 1863. By 1866, they added a hotel at the ranch.

Wiley’s

Robert and Margaret Wiley emigrated west in 1864. They operated several hotels and stage stops, including Nine Mile Ranch.

Wiley’s Station is in beautiful Dalzell Canyon, a narrow valley between the Pine Grove Hills and the Sweetwater Mountains. The California border runs through the canyon, leaving the flats just over the Nevada border.

Dalzell Station was a mile south, and Sulfur was three miles north.

Sweetwater Ranch Stage Stop

Sweetwater started as a stage station named Wahappa in the 1860s. A post office opened in 1870. By the early 1900s, Sweetwater had a population of fifty with two stores, a hotel and a saloon. The town became the supply center for mines in the Sweetwater Mountains.

Conway

The Conway family emigrated from Canada to the United States and were among the early settlers in the Bodie area. They were involved in ranching and hauling freight with wagons and teams of horses. At the Conway ranch, they had a stage stop and a bridge across the East Walker River. Burkham later purchased the ranch.

Through the early 2000s, an abandoned wood-frame house and outbuildings remained. These were destroyed, reportedly by the Forest Service.

Sonoma

Along the stage route, towns developed in later years. Following the discovery of the Sunny Jim mining district in 1906, developers planned the town of Sonoma.

By 1908, Sonoma applied for a post office. Building lots had been sold and construction began on buildings and a hotel. Newspapers reported that future residents would quickly snap up the remaining lots. An electric power plant on the river falls at Conway’s ranch was planned to power a 10-stamp mill.

The expected stampede to Sonoma never came. Reports from Sonoma and Sunny Jim mines disappeared after only a year. One of the few remnants of Sonoma is an abandoned cemetery. An archaeologist who studied the graves believed it was a Native American cemetery, not a settler’s.

Elbow Jakes

Elbow, also known as “Elbow Jake’s” stage station, was on the eastern side of the bend. It must have been a welcome sight for travelers dropping from the high desert to a lush river and meadows. During the 1860s, the station consisted of a house, stables and corrals for the stage line. In addition to the stage duties, the station’s keepers also kept a dairy and ranch, which provided Aurora with fresh meat and milk. Elbow operated a post office for a short period in 1881.

Nine-Mile Ranch & Station

Native Americans first used this site, and in 1844, John C. Fremont’s party camped at this approximate location en route to California.

After a rich silver and gold ore strike in 1860 on the border of Nevada and California, travelers needed a road to connect Genoa to the eastern Sierra mines around Mono Lake. Nine Mile Ranch became an 1860s stage stop on the Carson to Aurora road. It is most known for Mark Twain staying at the ranch to care for an ill friend.

On December 28, 2016, a series of 5.5 earthquakes seriously damaged the ranch house. It looked like the quake almost split the house in half. In 2018, the Ranch became part of the Walker River State Recreation Area.

The upstairs was taken apart stone by stone, and workers reinforced the downstairs stone walls with rebar. Each stone was labeled with a metal tag so it could be put back together in the exact same way. The plan is that the house looks like it did before the quake, at least from the front.

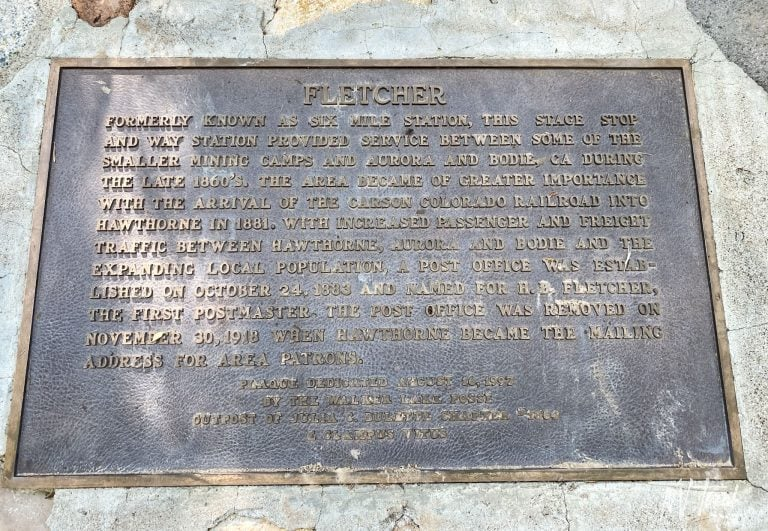

Fletcher

(Photo credit: This photo was provided by Harold Fuller)

H.D. Fletcher built Fletcher Station in the 1860s. During the Aurora and Bodie mining boom, the station served as an essential way station or “switching station” where teamsters and stagecoaches could trade out for fresh horses. The Fletchers also raised and sold fresh produce, as well as frogs and fish from their ponds.

A Post Office was established in October 24, 1883. H.D. Fletcher was named the first postmaster. The post office was in operation until November 30, 1913.

The station stop was renovated in 1949 into a restaurant, bar and sleeping quarters for hunters and fishermen. A fire started in the second-story chimney. The fire was quickly discovered, but with 10-year-old dry wood and a remote location, the building was soon engulfed in flames.

One volunteer firefighter beat the firetruck from Hawthorne to Fletcher. When he arrived, he found the victims had saved a few bottles of whiskey. They were sitting in chairs, sipping whiskey, watching the smoldering remains of the historic station.

Five-Mile House

From 1860 to the early 1900s, Five-Mile House changed owners and proprietors multiple times through the boom and bust of Aurora and Bodie. In 1880, the station’s proprietor shot an axe-wielding assailant intent on robbing the ranch.

The first mention of the site of Five-Mile House was on a 1860 map named Lone Star Rancho. Before the boundary survey, many thought the location was the border of California and Nevada. Later that same year, Sam Young wrote that he had stayed at the same approximate location at Evans Ranch.

A survey of the Nevada Territory in 1862 was the first to use the name 5 Mile Ranch. A reporter for the Daily Alta California in 1863 wrote of Five Mile House. He mentions it was at the last grade before ascending to Aurora and had “better natural mountain roads” than he had seen before.

The stage route changed in 1878, bypassing Junction House and stopping at Five Mile House. E.J. Curtis was the proprietor and would “cater to the welfare of his guests and travelers.”

Trouble knocked on Baldwin’s door in the spring of 1880. A Norwegian named Andy hit the front door of the hotel with an axe. Andy “was on a jamboree and threatened to clean out the ranch.” He broke through the front door in a way that would make Jack Nicholson in The Shining proud.

Baldwin responded by firing a shotgun at Andy, striking his shoulder. The hole was large enough to fill with a duck egg. The doctor was called, and it was determined the injury was not fatal. Baldwin surrendered to the Sheriff, but was released.

Learn more about Five-Mile House.

Magnum

Just outside of Aurora, the Aurora Consolidated Mining Company operated a 500-ton mill beginning in 1914. One of the owners was a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and strongly disagreed with the saloons and brothels. They established a company town that prohibited any business they deemed immoral.

The mill worked old mines and tailings, resulting in $1.8 million. It closed in 1918, and the buildings and equipment were relocated to Goldfield. The foundation remains, but modern mining has obliterated the town.

Aurora

In 1860, a trio of miners discovered ore near the Nevada/California border, and the town of Aurora was born. Within a year, 1,400 people called Aurora home. The town included almost 800 homes, twenty stores, and twenty-two saloons.

Aurora was the epitome of the Wild West. Men slung pistols on their hips, and conflict often resulted in gunfights. Entertainment included saloons, brothels, and dog-vs.-badger fights. Half the women in town were prostitutes, many from China. Samuel Clemens, later known by his pen-name Mark Twain, lived and mined in Aurora from spring to fall of 1862.

(Photo credit: UNLV)

Aurora has a unique distinction: it was the county seat for two counties. When California became a state in 1850, the 120-degree west longitude was its eastern border. On six occasions from 1855 to 1900, surveys attempted to locate the 120-degree longitude, each with different results—the boundary discrepancy led to multiple issues. In Aurora, the town was simultaneously the county seat of Esmeralda County, Nevada, and Mono County, California. On Election Day, residents voted in Esmeralda County and then walked to the next polling station to vote in Mono County. In 1863, Aurora lost the Mono County seat when it was officially determined to be in Nevada.

Aurora faded as quickly as it boomed. By 1864, half of the town’s mills had ceased operations, and six years later, half of the houses had been abandoned.

Aurora experienced several revivals, including the 1870s, with mining in Bodie. In 1883, the town, once the seat of two counties, lost the Esmeralda County seat to Hawthorne; the post office closed in 1897. Aurora experienced a final revival in the early 1900s with an uptick in mining. The post office reopened in 1906, and electrical power arrived in 1910. This cycle lasted a decade. In 1918, the school closed, followed by the post office the following year.

Blanchard Toll Road

In 1862, nine miners were awarded a franchise to develop a toll road connecting Bodie to Aurora and eventually to Genoa. The road wound through the narrow Bodie Gulch, where, in places, sheer rock walls soar to the sky, allowing in only a sliver of sunlight.

Between the 1880s and 1890s, Hank Blanchard operated the toll road. Blanchard had two stage stops: Blanchard’s and Sunshine Station. Blanchard’s Station was midway between Bodie and the state line, and Sunshine Station was halfway between Bodie and Aurora, earning it the alternate name Halfway House. Two to three stages ran daily in each direction.

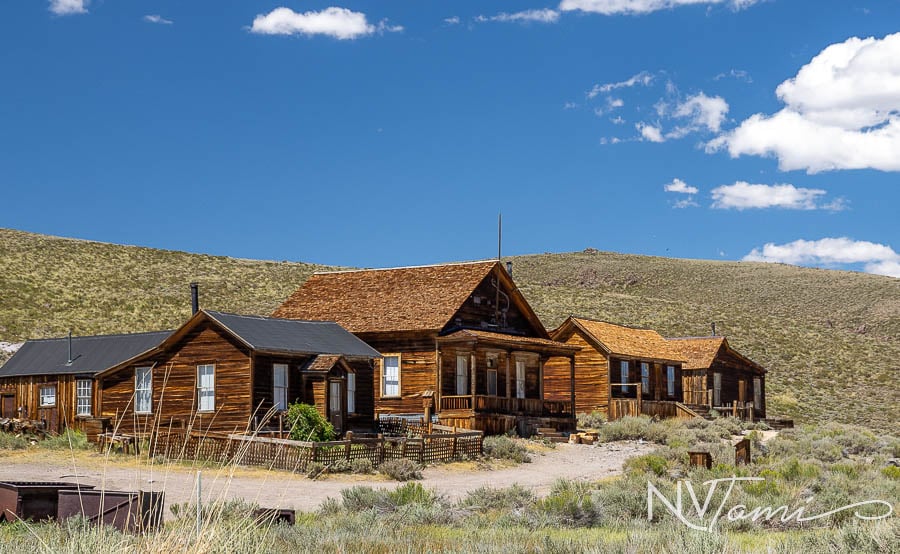

Bodie

Bodie started as an unassuming mining camp following the discovery of gold by W.S. Bodey in 1859. Tragically, Bodey froze to death in a winter storm while trying to reach Monoville for supplies, and the town was named in his honor. While nearby Aurora boomed, Bodie remained a small camp. By 1868, the town’s two-stamp mills ceased activity.

The Standard Company found gold in 1876. Within a few years, Bodie boomed and boasted a population of 10,000. Services rivaled big cities: banks, unions, newspapers, a railroad, and even a brass band. Nine-stamp mills were in operation, shipping bullion to the mint in Carson City, Nevada.

Bodie’s mines declined after 1910, and by 1920, only 120 people remained. Miners continued to operate until the start of World War II when the US War Production Board issued Order L-208, which halted all mining that didn’t support the war effort. Bodie’s post office closed in 1942.

WANT MORE GHOST TOWNS?

For information on more than five hundred ghost towns in Nevada & California, visit the Nevada Ghost Towns Map or a list of Nevada ghost towns.

Learn about how to visit ghost towns safely.

References

- ECV: Wilsonville

- Nation: Nyles. . Pine Nut Press, 2000.

- Nevada Historical Society: Wagon transport in Nevada: Wagon freights and stagecoaches 1860-1895

Leave a Reply