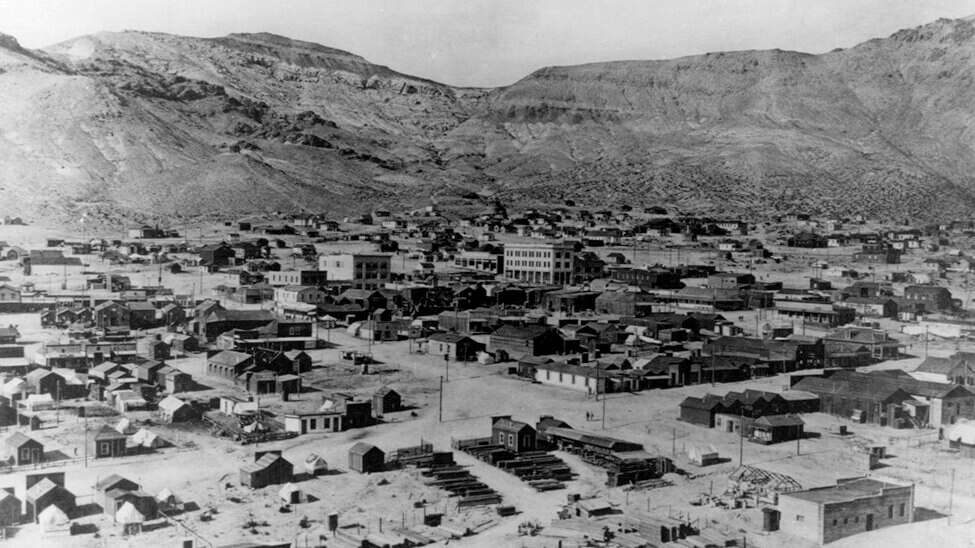

Rhyolite is a diamond in the desert and one of Nevada’s best ghost towns. It is the epitome of the boom-to-bust mining town. In five years, it went from nothingness to a modern town, then to only a handful of remaining residents and finally to a complete ghost town. Rhyolite wasn’t just any Nevada town; it was once one of the largest in the state, with every imaginable amenity. The collapse was as rapid as the growth, with some buildings not complete until after the decline started.

Today, Rhyolite is one of Nevada’s most visited ghost towns for a good reason: The remaining structures are iconic and photogenic. You can spend an entire day walking the streets of Rhyolite and imagining what it was like to experience the growth and death of such a beautiful town in less than a decade.

Shorty Harris and the Bullfrog Boom

Famed Death Valley prospector Frank “Shorty” Harris and Ernest “Ed” Cross discovered the Bullfrog District in 1904. Standing only a few inches over 5 feet tall led to Shorty’s nickname. Legend says Shorty could smell gold and was responsible for many mining booms, including Bullfrog. Shorty didn’t work the claims he discovered; he quickly sold them to investors. He went to town, celebrated his find at the saloon, spent all his money and went on the hunt for gold again. His headstone in Death Valley reads, “Here lies Shorty Harris, a single blanket jackass prospector.”

(Photo credit: National Park Service)

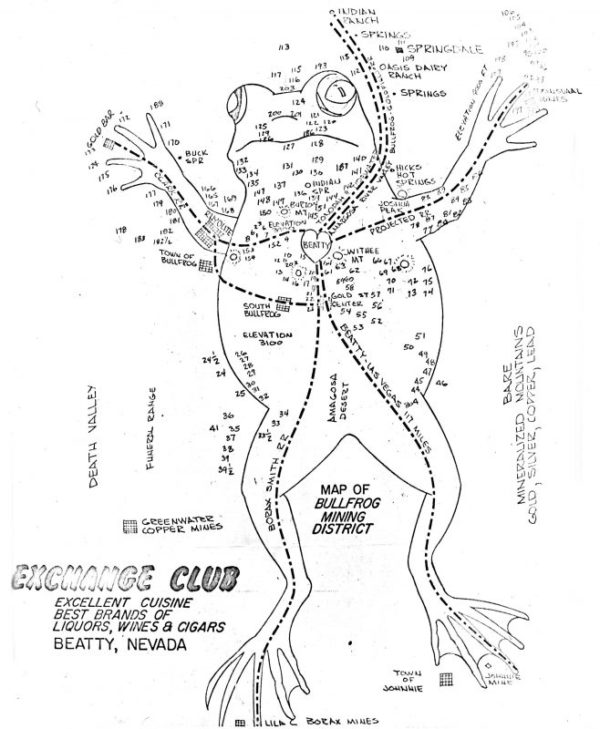

The naming of the Bullfrog district has several theories. One is that it is named after the aster green rocks, one of which may have resembled a frog. An alternative theory is that Ed Cross enjoyed singing the song “The Bull-dog” (sp), which included the line “Oh! The bulldog on the bank and the bullfrog in the pool.” The song was not published in Songs of Service until 1918 but could have predated the discovery of the Bullfrog. Some believed the district was well, bullfrog-shaped, with Beatty at the heart.

(Credit: Nevada Magazine)

With the Comstock Bonanza starting in 1858, over 60,000 people moved to Virginia City and surrounding areas. The rich ore funded the Civil War and Nevada was granted statehood and became known as the Battle Born state. Following the Civil War and the mining bust, Nevada’s population decreased to 40,000. Some even proposed to remove Nevada’s status as a state and return it to a territory. The Bullfrog district, Tonopah, and Goldfield pulled Nevada out of the thirty-year depression.

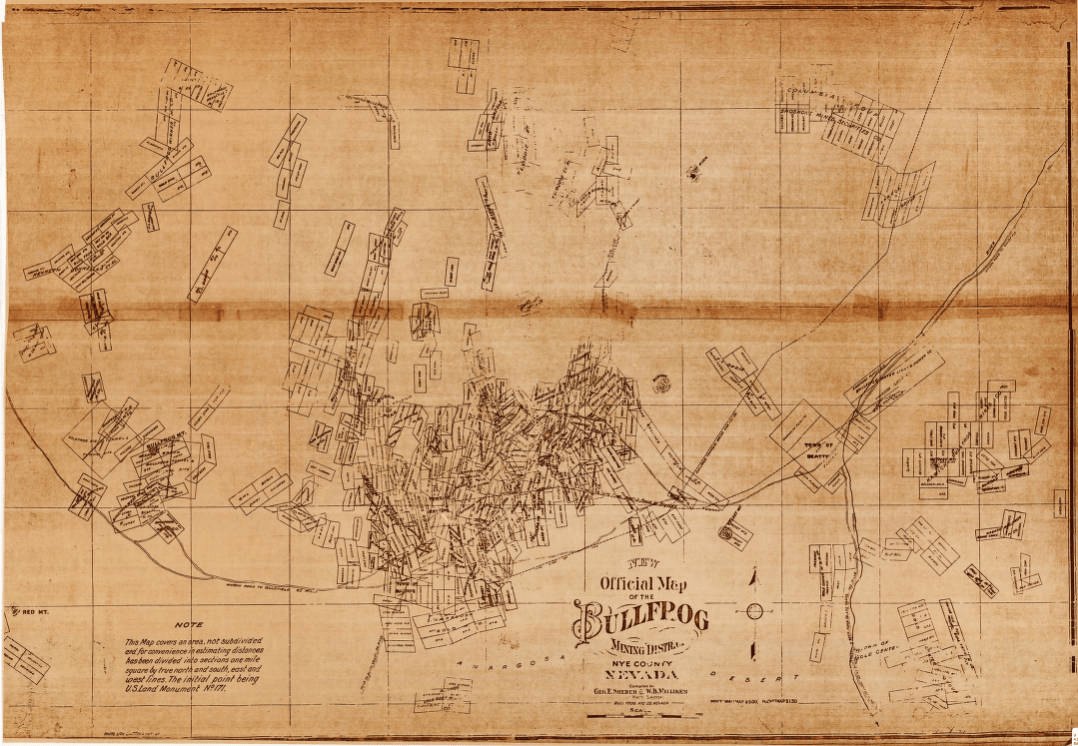

Shorty Harris and Ed Cross discovered the Bullfrog district on August 9, 1904, and the rush was on. Towns sprung up over the region, and many relocated with the discovery of new strikes. It is said that someone could leave for a few days, and when they returned, the entire town was in a new location.

I’ve seen many gold rushes in my time that were hummers, but nothing like that stampede.

Frank “Shorty” Harris

(Photo credit: Legends of America)

The Bullfrog boom didn’t last a decade and soon the area, well, croaked.

The boom-to-bust cycle and relocation of towns mean the Bullfrog district is rich in another resource: ghost towns. While many ghost towns dot the Bullfrog District, Rhyolite remains the diamond in the desert and is one of the most photographed ghost towns in the United States.

Rhyolite

While many mining towns sprout from nothing and grow little beyond a tent or rustic town, Rhyolite became the diamond with “city airs” in the rough desert environment.

Butler, Nevada · Saturday, March 18, 1905

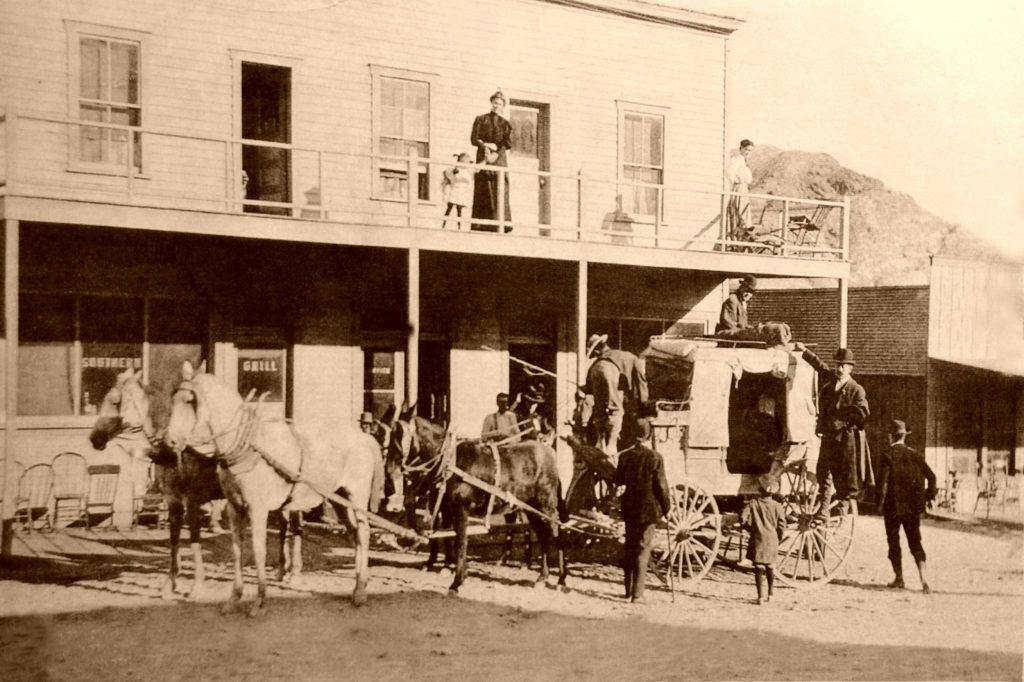

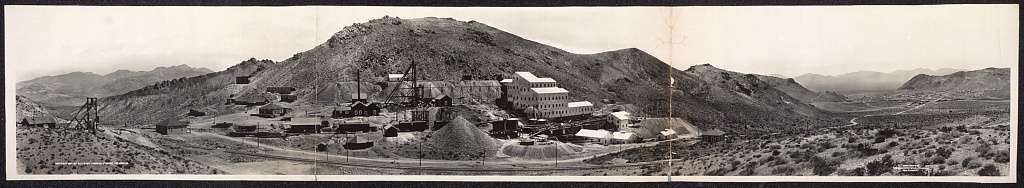

In 1905, developers planned Rhyolite close to the largest mines. While it started with a few tent boarding houses, stores and saloons, soon a buildings of wood and stone emerged.

(Photo credit: Travel Nevada)

Steel Magnate, Charles M. Schwab purchased the Bullfrog Mining District in 1906. Soon, three trains arrived at the beautiful new California-Mission style train station: Las Vegas & Tonopah, the Tonopah & Tidewater, and the Bullfrog-Goldfield.

Butler, Nevada · Saturday, July 28, 1906

Rhyolite wasn’t just any rough and tough mining boom town; it had every convenience of a big city: telephone, electric street lights, and concrete sidewalks. They had an opera house with an orchestra, newspapers, swimming pools, 50 saloons and a red-light district for entertainment.

Financial issues

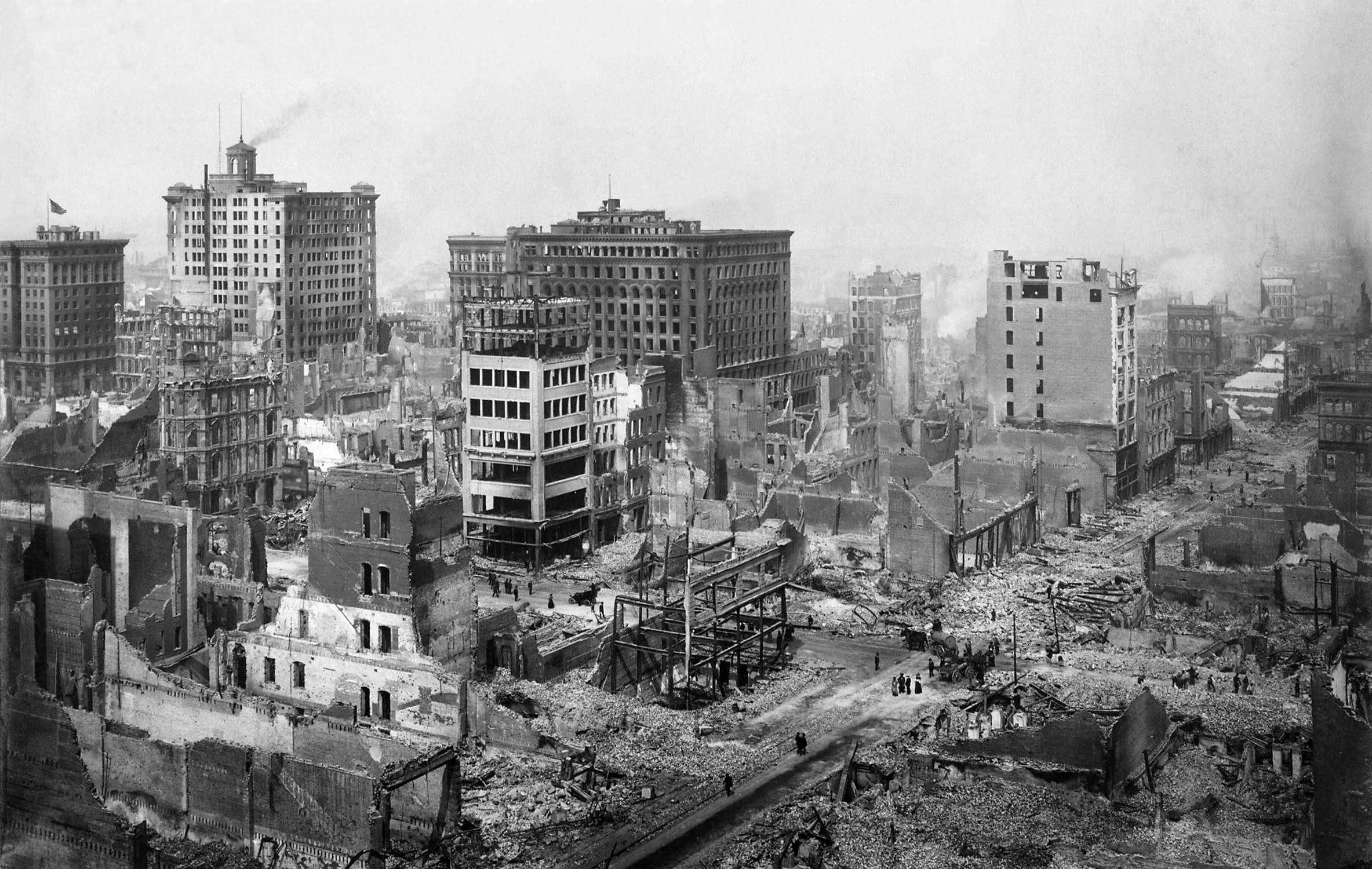

Almost as quickly as Rhyolite boomed, it faded into a ghost town. The Great Earthquake of 1906 in San Francisco had far-reaching effects. The 7.9 earthquake and resulting fires destroyed 80% of San Francisco and over 3,000 people lost their lives. Many lost their assets and ability to invest in Rhyolites mines.

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Panic of 1907 was a financial crisis in which the New York Stock Exchange dropped 50% from the prior year, causing nationwide bankruptcy for businesses and banks. The following year, an independent study showed that Rhyolite’s mines were overvalued, and stocks plummeted. By 1910, Rhyolite’s mines were operating at a loss and closed in 1911. Between 1907 and 1910, the district produced an astonishing $1,687,792, over $56 million in 2025 terms.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress)

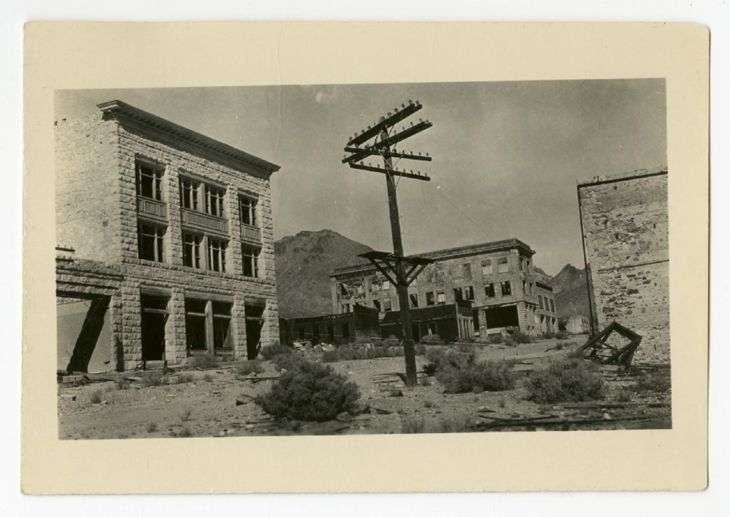

Rhyolites population paralleled the collapse of the mining industry. Soon, only 1,000 called it home; by 1920, only 24 people remained. Within four years, they, too, moved to abandon the town, which declined as rapidly as it came to life.

With the fall of Rhyolite, Beatty relocated many buildings, including the Miners Union Hall, now the Old Town Hall in Beatty, and the Rhyolite school’s roof now adorns the Beatty schoolhouse. Construction material was repurposed, including doors for Dun Glen, and the saloon bartop moved to the Pioneer Saloon in Goodsprings.

Living the Twilight Zone

Spend a day walking the streets of Rhyolite. Imagine what it was like to experience the growth and death of such a beautiful town in less than a decade.

You start by living in a tent with an oil lamp for light and a campfire for heat. Then you move into a beautiful modern home with electricity, a fireplace and even a telephone.

Initially, you ration your precious water brought in by the barrel. Before long, you have three public swimming pools to choose from, at least one of which changes all the water nightly.

In the early times, you spend the days working your claims and evenings at the saloon. Soon, you are dressing up and attending fraternal organizations, social clubs, and the opera.

Then, within 5 years, it’s all gone. Your neighbors say goodbye and move on to new prospects.

The beautiful new train station sees only departures. The school’s roof, which was never completed before many children left, is lifted off the walls and shipped to Beatty. Entire buildings have been lifted onto skids and drug out of town. Beautiful businesses like the Cook Bank are taken apart piece by piece and scattered across the region.

You walk around town, once teaming with life, now only marked by the occasional bray of a burro. It must have been life living an episode of the Twilight zone.

Visiting the ghost town of Rhyolite

With the advent of automobiles, Rhyolite became a popular tourist destination in the 1920s. Tourism dropped during World War II but rebounded following the war. The Bureau of Land Management maintains Rhyolite.

Today, Ryholite is one of Nevada’s most visited ghost towns. This is for a good reason; the remaining structures are iconic and photogenic. You can spend an entire day walking the streets of Rhyolite. Many locations have an informational sign about what once stood at that location. Below are the must-see and the well-known buildings. The majority of the buildings are on Golden Street. They are in order driving from Highway 374 north through town.

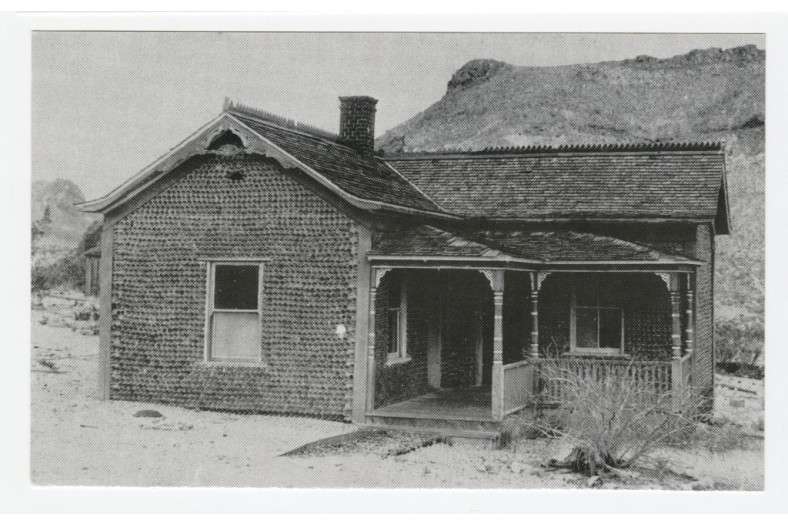

Tom Kelly’s Bottle House

The Bottle House isn’t the only house made of bottles in Nevada, or even in Rhyolite, but it is the most famous. Tom Kelley (or Kelly) built this house using used beer bottles. He constructed the house using an estimated 50,000 bottles. Children collected and were paid 10 cents for a wheelbarrow of bottles. Plaster and wallpaper cover the interior walls.

John auctioned the 3-room house for $5 per ticket with 400 sold. The Bennett family won the raffle and lived in the house from 1906 to 1914. The bottle house was used as a location for several film shoots, including The Air Mail. As the film company removed the rear wall for filming, the company repaired and stabilized the unique home.

Rhyolite School

As the town grew, it quickly needed a school. Lacking funds, citizens held dances to raise money. They built a small school that barely survived a windstorm in 1906. Social events and trustee personal funds raised money for a second schoolhouse. The school served 74 children, with one teacher; the other almost 200 Rhyolite children could not attend.

In 1907, bonds funded a new school that could serve all the children. The school did not open until 1909 after Rhyolite started its decline, and many children had already moved on. It took residents of Beatty until 1978 to pay off the bonds.

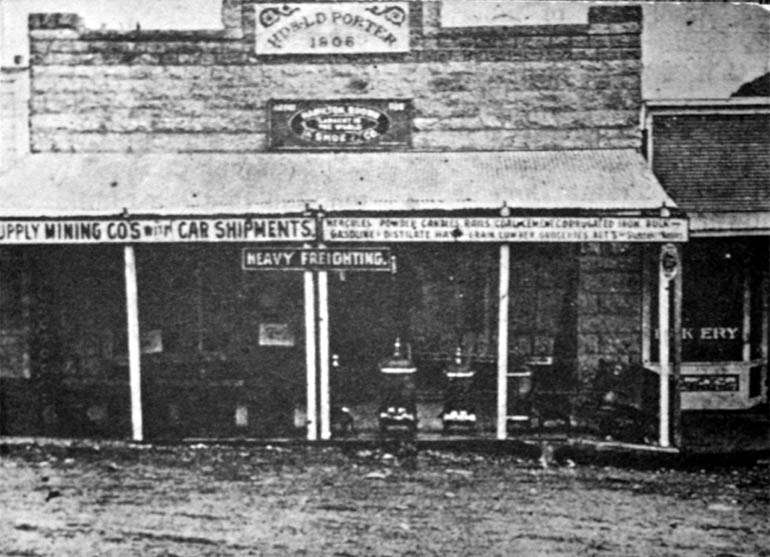

Porter Brothers Store

Hyram, “H.D.” and Lyman, “L.D.,” Porter had a store in Johannesburg, California, but wanted a presence in the new boomtown. They started with a store on Main Street, but the size wasn’t adequate for their large selection of groceries, supplies and furniture.

In 1906, they built a beautiful stone building on Golden Street, costing over $10,000. This store had three stories: a basement, the main level, and a gallery above. To celebrate the opening at the new location, the brothers had a 3-day sale at their old location and hosted a ball at the new store featuring an orchestra and refreshments.

The brothers expanded their offerings to include a home furnishings store at their original location, a warehouse and a lumber yard. They had stores in Rhyolite, Beatty, and Keane Springs. Hyram was one of the last to leave Rhyolite, acting as the postmaster until 1919.

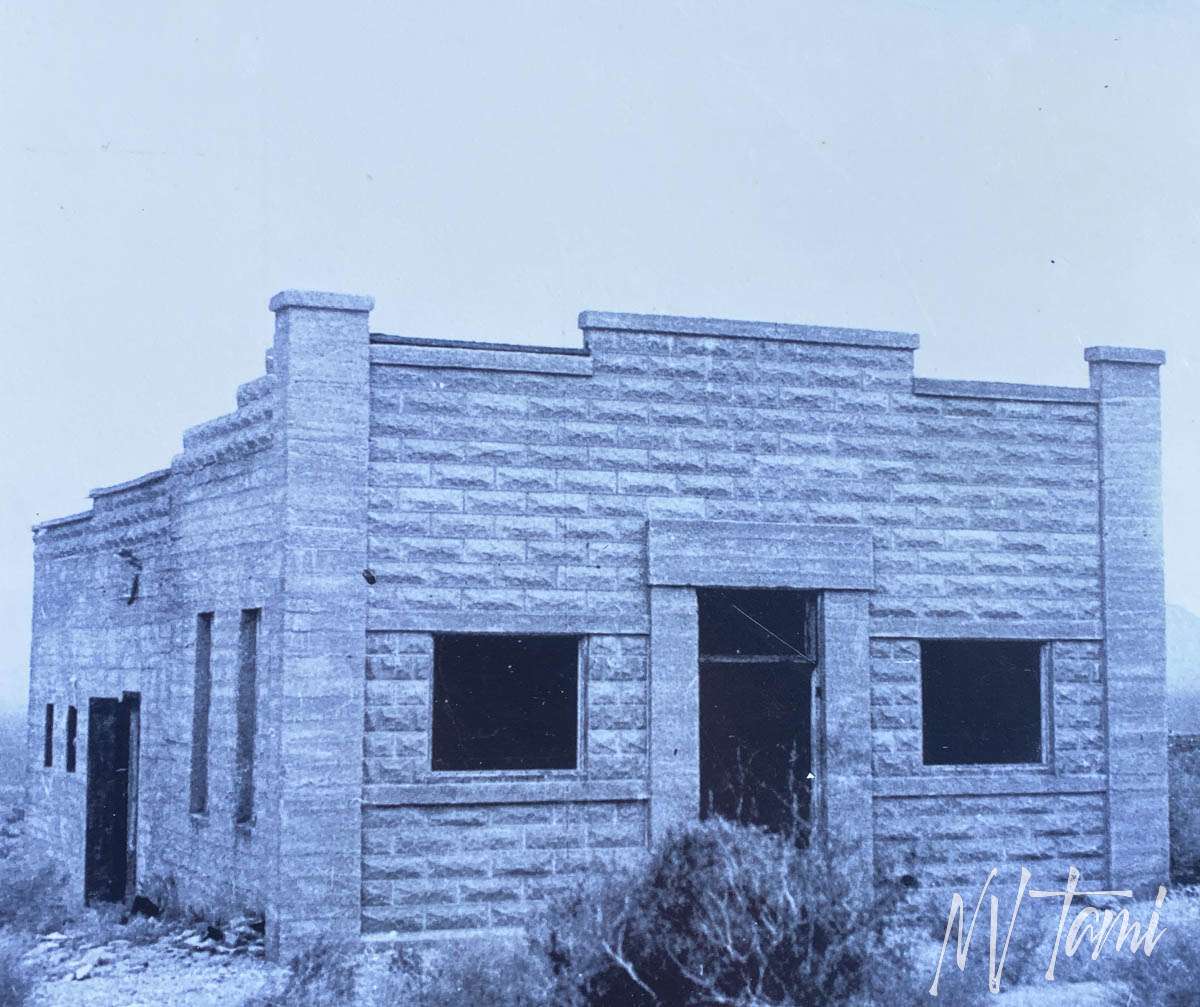

Overbury Building

John Overbury moved from Oakland, California, to Rhyolite, where he built a house for his new bride, including a telephone. He purchased a lot for his office building and planned a two-story structure. Learning of the three-story plans for the Cook Bank and not wanting to be outdone, he added an additional story.

(Photo credit: USU Digital History)

The main floor was one space with several offices. The second and third floors contained offices. It boasted private restrooms, fireproof shutters, and fire extinguishers.

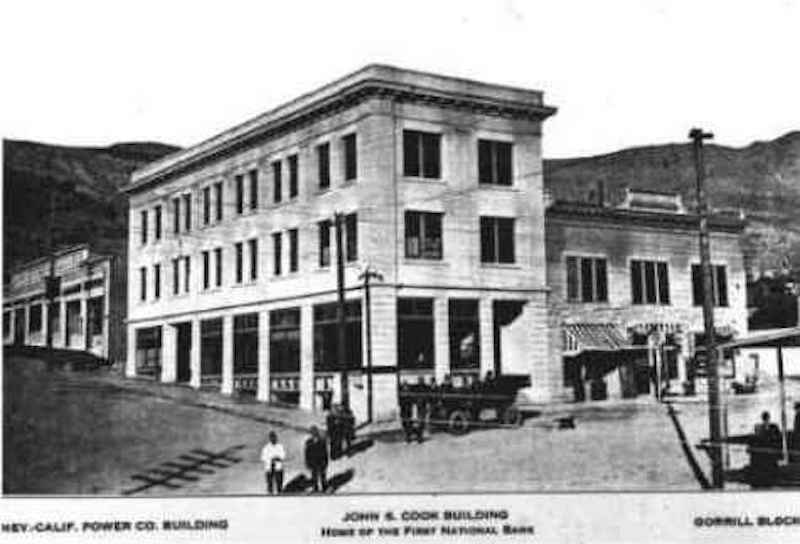

Cook Bank Building

In 1905, John S. Cook, his brother, opened the John S. Cook & Company Bank in Goldfield. Soon, they opened a branch in Rhyolite in a rented location on Main Street.

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)

The Cook bank was one of four in Rhyolite. The John S. Cook & Company Bank built a substantial three-story building, fronted with plate glass and iron: a marble staircase, mahogany, electricity and indoor plumbing. The bank was on the main level, offices were upstairs, and the post office was in the basement.

The Cook Bank survived the Financial Panic of 1907 but soon merged with the First National Bank of Rhyolite. The bank closed in 1910, selling many interior fixtures at a considerable discount.

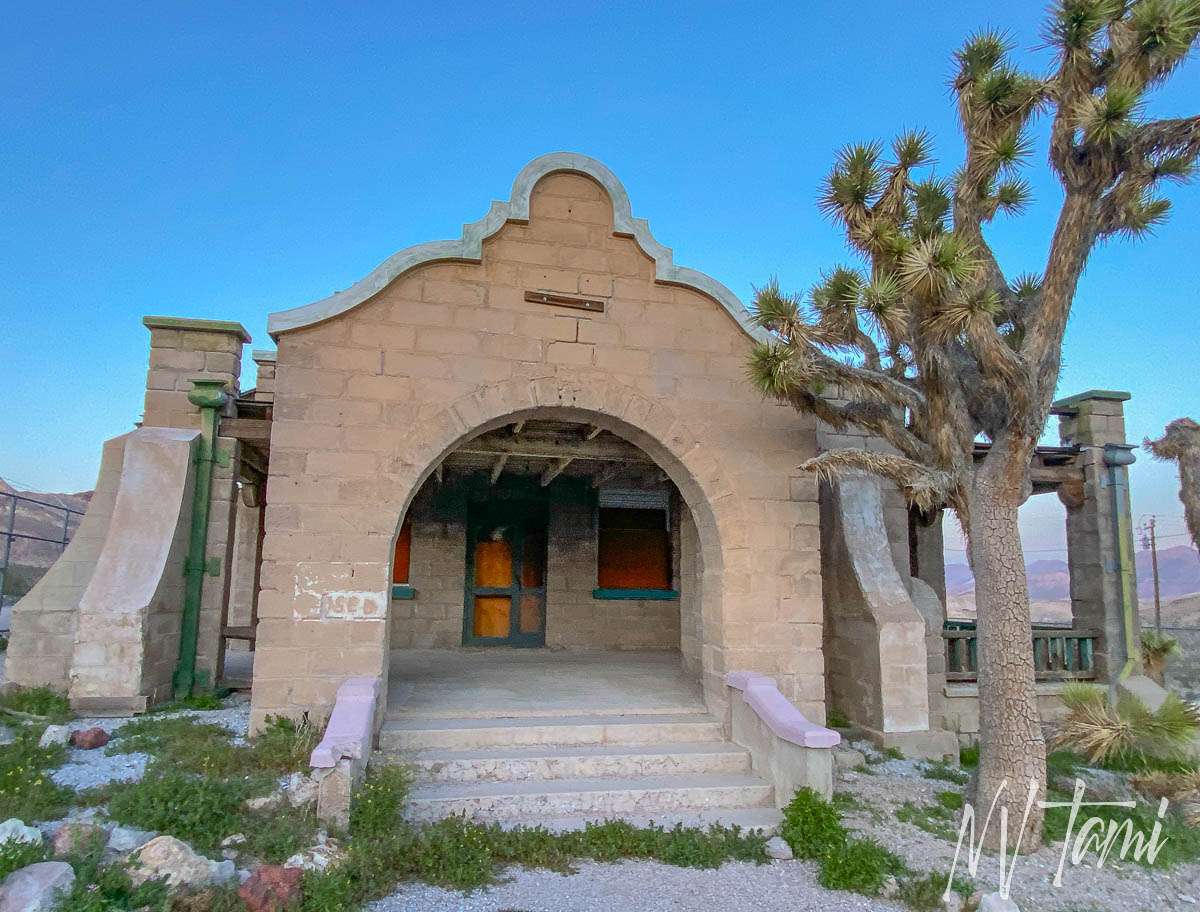

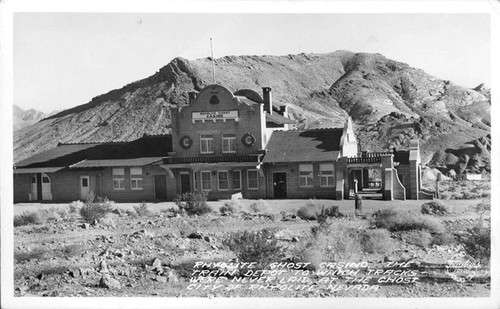

Train Depot

Rhyolite boasted something few towns could: three railroads.

The Las Vegas & Tonopah was the first to serve Rhyolite, arriving on December 14, 1906, loaded with 100 passengers. The line soon brought 50 freight cars daily and needed a depot to support their activity level.

In September 1907, they started construction on the beautiful and ornate Mission Revival-style depot. It had separate men’s and women’s waiting areas, a ticket office, a baggage area and an apartment for the ticket agent. Completed in 1908, it cost $130,000, $4.5 million in 2025!

(Photo credit: Calisphere)

By the time the station was completed, Rhyolite was in decline, and more people were departing Rhyolite than arriving. In 1935, Wes Moreland purchased the depot and converted it into the Rhyolite Ghost Casino. Gambling and drinks were on the main floor. Some say that the upstairs brought the red-light district back to life. The depot had many owners over the years before being acquired by the Bureau of Land Management.

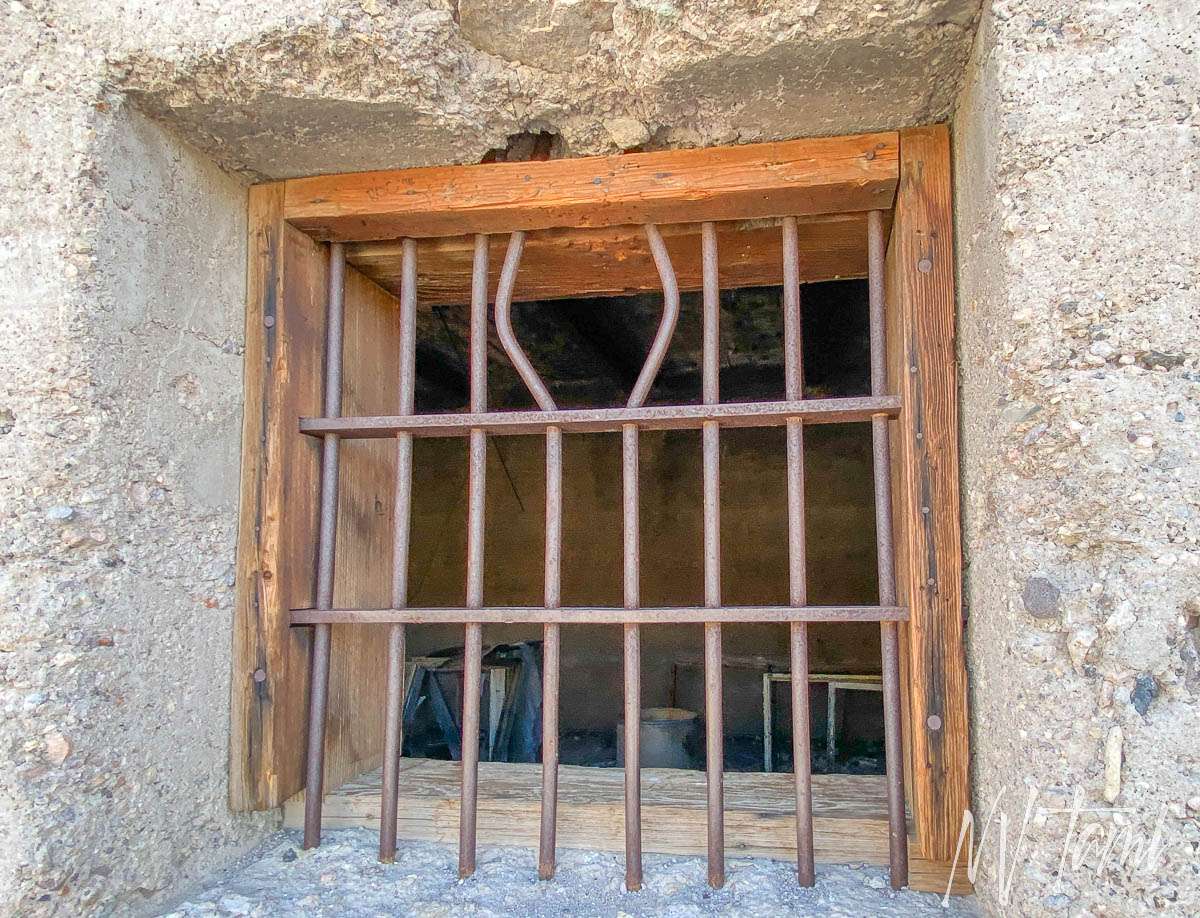

Jail

While Rhyolite wasn’t known as a rough and tough Wild West town, it had a fair share of crimes. December 15, 1904, was Rhyolite’s first shooting, where two men fired on each other at close distance. The local physician said the men were good, yet they both ended up dead.

(Photo credit: BLM informational sign)

The closest jail was in Bullfrog, which cost $15 per trip to transport prisoners from Rhyolite. Not wanting to pay for the move, In 1907, the county built a jail in the red-light district. The four cells were generally enough for Ryholite’s needs, but they couldn’t hold 49 striking Austrians in Bonnie Claire.

The most famous prisoner was Llewellyn L. Felker, aka Fred Davis, who murdered his girlfriend, Mona Bell. Felker was held in the Rhyolite jail but moved due to the fear of a lynch mob. They were correct in their assumptions; a posse started the next night only to find Felker moved to Beatty and later Tonopah, where he was convicted of second-degree murder.

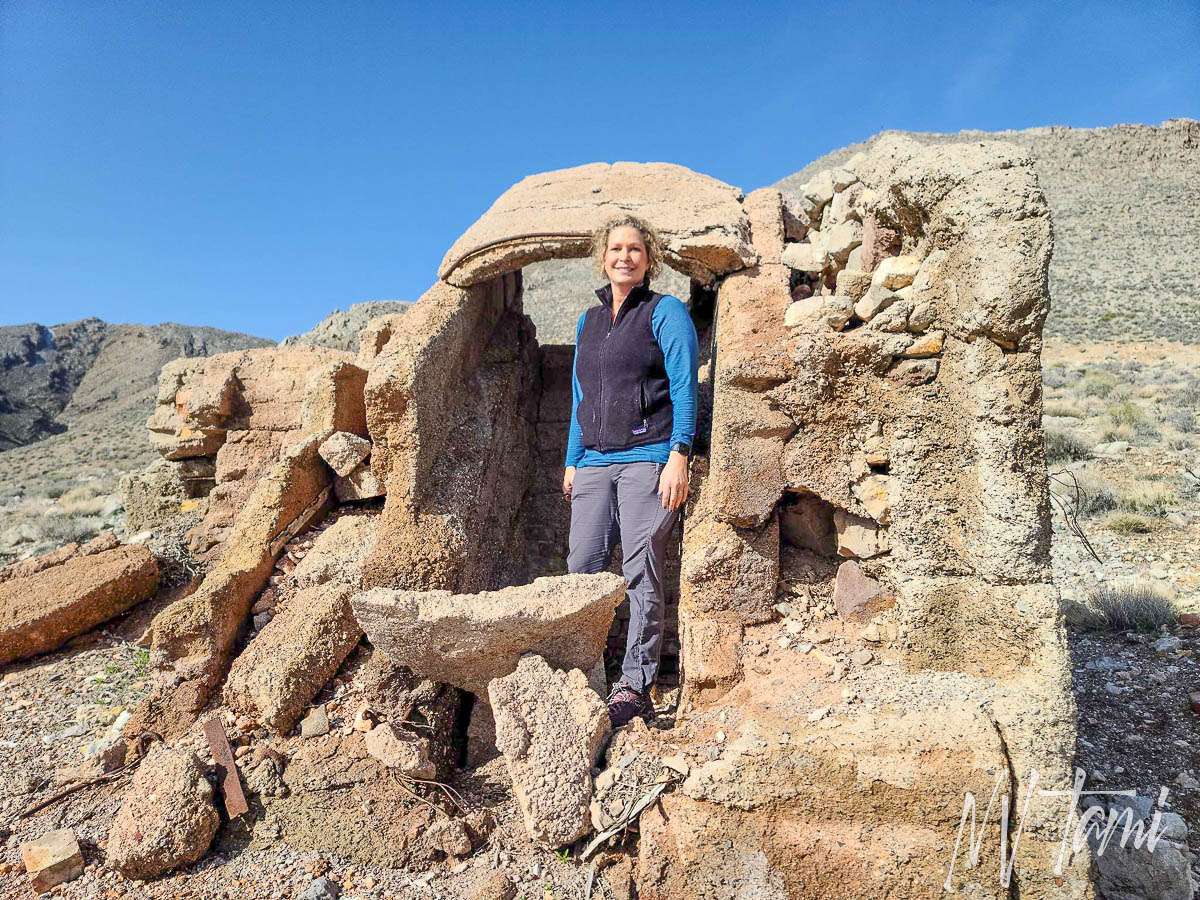

Miner’s Cabin

The “cast-in-place rubble and adobe” is one of Rhyolite’s few remaining structures. Located by the red-light district, some believe it was a brothel, while others think it was used by railroad workers due to the location by the tracks.

(Photo credit: BLM information sign)

Mona Bell’s “Grave”

A popular spot that draws visitors is the “grave” of Mona Bell. Visitors have left booze bottles, trinkets, high-heeled shoes, and flowers. As the story goes, Mona was a beloved prostitute murdered by her pimp. The townswomen didn’t want her in the proper cemetery, so they buried her by the red-light district.

Some of the story is true, but Mona Bell’s grave is in Washington. Mona Bell was born Sarah ‘Sadie’ Isabelle Peterman in Battle Creek, Nebraska, in either 1886 or 1887. Her partner, Llewellyn L. Felker, aka “Fred Davis,” murdered her on January 3, 1908. He was held briefly in the Rhyolite jail but quickly relocated, fearing a lynch mob.

The real story has more twists and turns than the story of her fictional grave in Rhyolite. It involves multiple aliases, Mona Bell’s husband (not Davis), Davis’ wife (not Mona Bell), jailbreaks, additional murders, a prison break and bootlegging! Stay tuned; I’m partway through the period newspapers and unwinding the sordid tale.

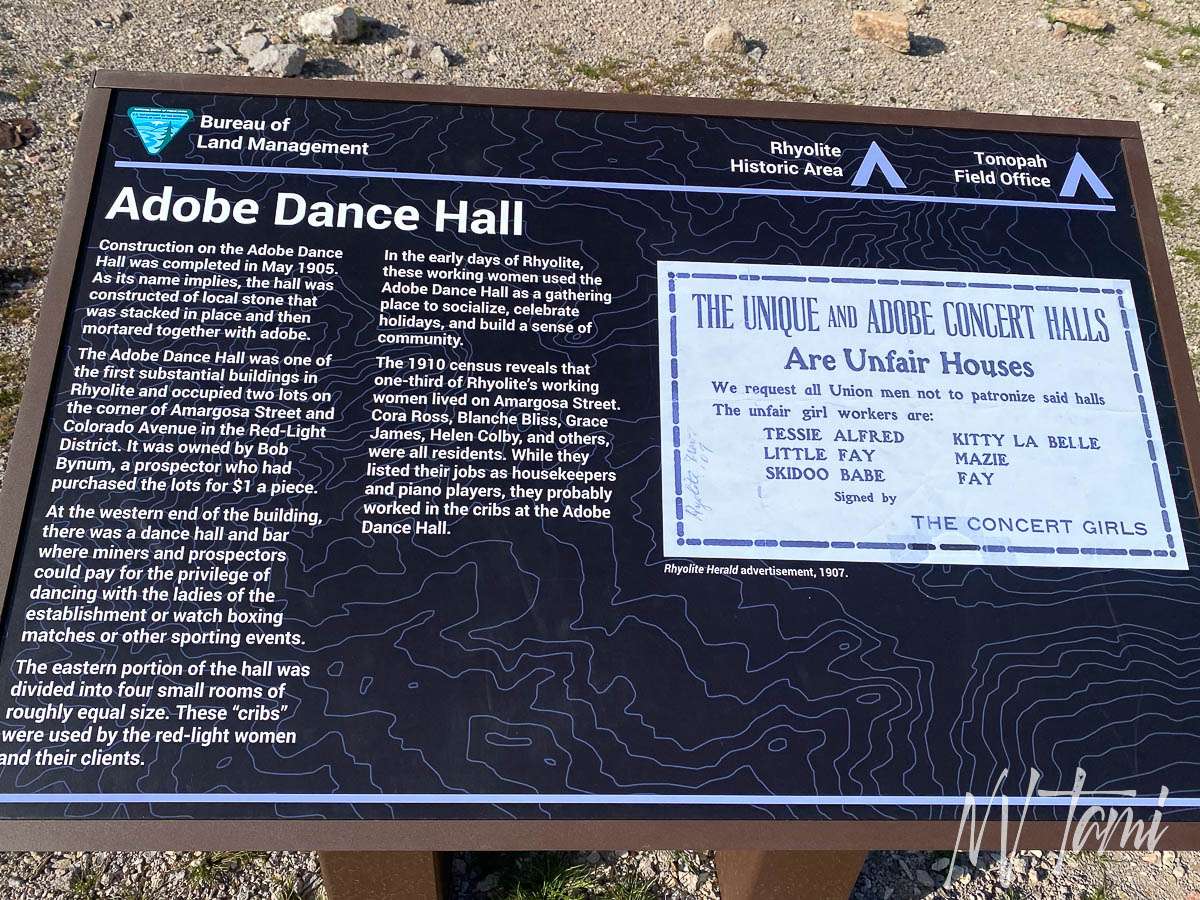

Adobe Dance Hall

One of the early buildings in Rhyolite was the Adobe Dance Hall. Bob Bynum built the hall in 1905 with stacked stone and adobe. The large hall sat on two lots on the corner of Amargosa Street and Colorado Avenue.

Adobe Dance Hall was in the red-light district. The term “red light” has several possible origins. Some say it was named after the “Red Light House Saloon” (brothel) in Dodge, Kansas. Another theory is that railroad workers left their lit lanterns with a red light outside of the brothel so that they could be found during an emergency.

One side of the hall was a bar and hall where men could pay for a spin around the floor with a dance hall girl. The other side was four cribs, which were a step down from the brothels. Prostitutes rented cribs where they lived and worked, often overseen by a pimp. The rooms were sparsely furnished, having only a bed, pot-bellied stove and a water bucket. Girls sat in the windows to advertise their services. A busy “working girl” could see up to eighty men an evening. The ladies of the evening used Adobe Dance Hall to socialize with each other.

Cemetery

The Bullfrog/Rhyolite cemetery was in use between 1904 and 1912. Aside from a memorial, most graves and headstones have faded into the desert. While some are marked with names and dates, many only have a cross made of wood or rock or are unmarked.

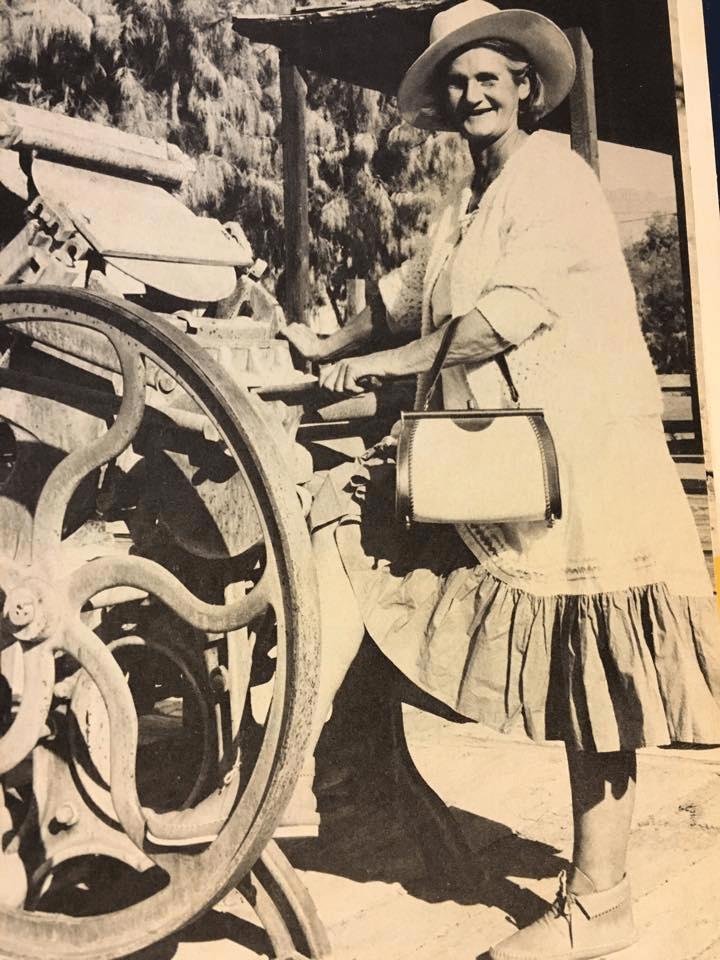

Panamint Annie

Panamint Annie is a legend in Death Valley. A large Joshua tree shadows the grave. A simple square granite headstone marks her final resting place. “Mary Elizabeth Madison known as Panniment Anne, 1910-1979.” (Annie and Panamint are misspelled; Death Valley National Park and her Great-granddaughter confirmed her nickname was Annie, not Anne.)

Visitors have left a variety of mementos, including flowers, coins, candy, toy cars, and lots and lots of booze bottles. Panamint Annie would have approved of the latter.

Learn more about the amazing Panamint Annie.

Goldwell Open Air Museum

While it isn’t a ghost town, you can’t visit the area and not stop at the Goldwell Open Air Museum. The museum is free but accepts donations. They have a small museum of historical photographs from Rhyolite.

More Ghost Towns around Rhyolite

If you have more time to explore, the Bullfrog district has many more ghost towns. Beatty is known for two things, as a gateway to Death Valley and the ever-popular road trip stop, the Death Valley Nut and Candy Company. Travelers fill the hotel rooms at night but leave early the next day to continue their journey between northern and southern Nevada or head into Death Valley National Park. Some visit the spectacular ghost town of Rhyolite, but otherwise, few explore the surrounding area. Many don’t realize that ghost towns surround Beatty, enough to keep you exploring for days.

WANT MORE GHOST TOWNS?

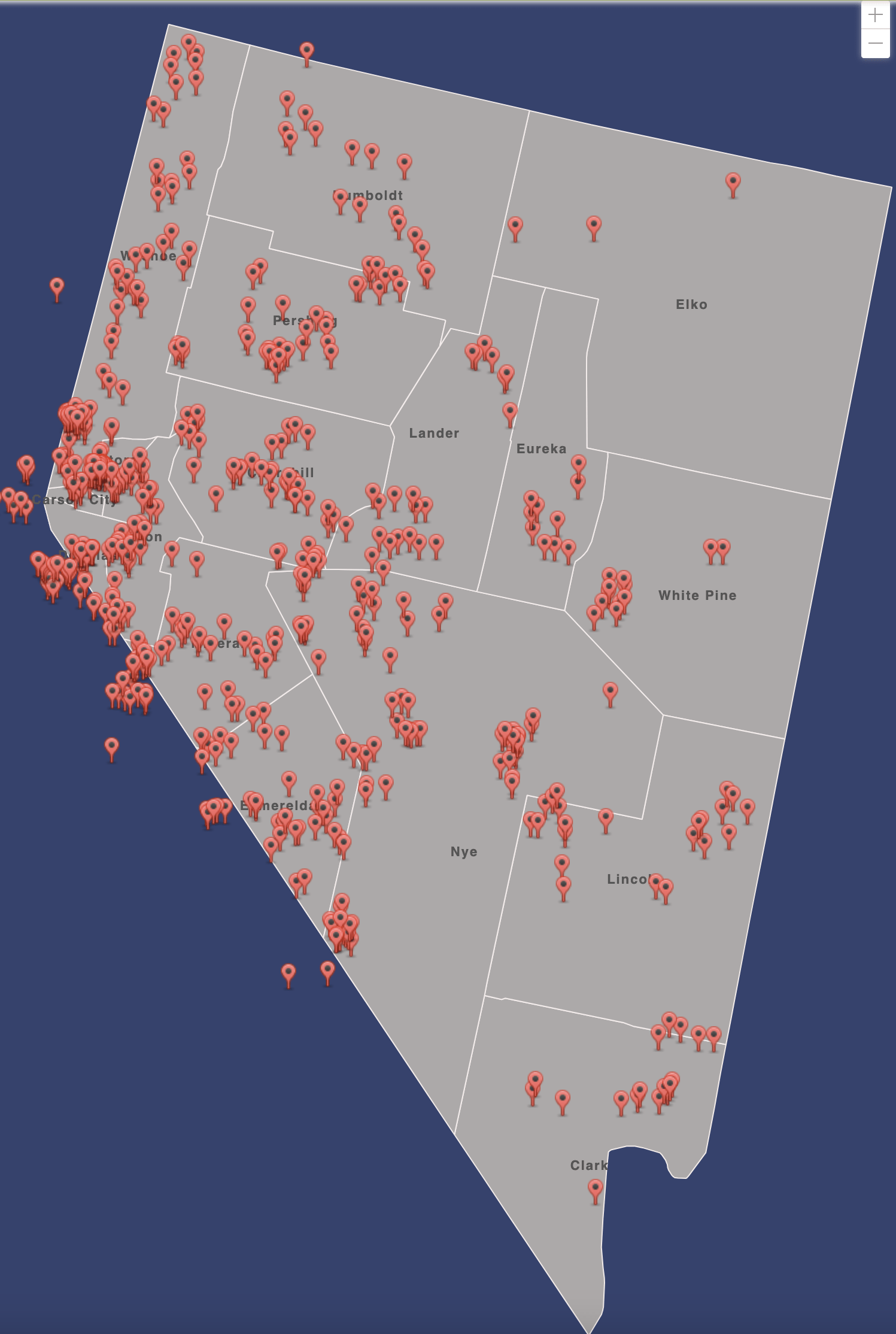

For information on more than five hundred ghost towns in Nevada & California, visit the Nevada Ghost Towns Map or a list of Nevada ghost towns.

References

- Carlson, Helen S. Nevada Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary. University Nevada Press, 1974.

- Gamett, James and Stanley W. Paher. Nevada Post Offices: An illustrated history. Nevada Publications, 1983.

- The Goldfield News and Weekly Tribune Jul 14, 1905

- The Goldfield News and Weekly Tribune Jul 14, 1905

- The Goldfield News and Weekly Tribune Jul 14, 1905

- The Goldfield News and Weekly Tribune Sep 29, 1905

- The Goldfield News and Weekly Tribune Dec 29, 1906

- The Goldfield News and Weekly Tribune Apr 3, 1909

- Hall, Shawn. A guide to the ghost towns and mining camps of Nye County, Nevada. Dodd, Mead and Company, 1981.

- National Park Service

- Paher, Stanley W. Nevada Ghost Towns & Mining Camps. Nevada Publications, 1970.

- Pahrump Valley Times: The legend of the Rhyolite grave of Mona Bell

- Pahrump Valley Times: Mona Bell’s grave a Rhyolite tale born of legend

- Patera, Alan H. Rhyolite: The Boom Years. Western Places, 2014.

- Reno Gazette-Journal Feb 20, 1908

- The Sacramento Bee Mar 26, 1908

- Tonopah Bonanza March 18, 1905

- Tonopah Bonanza July 28, 1906

- Tonopah Daily Bonanza Jan 5, 1908

- Tonopah Daily Bonanza Jan 5, 1908

- Tonopah Daily Bonanza Jan 7, 1908

- Tonopah Daily Bonanza Feb 25, 1908

- UNLV Special Collections

- The Union December 18, 1920

- Yerington Times Apr 11, 1908

Steve Whitehorn says

Thanks Tami for this story and great collection of well framed pictures. Your sunset portrait is awesome.

Tami says

Thanks, glad you enjoyed it. When Austin told me to freeze, I thought there was a rattlesnake! He saw me in the sunset and grabbed the pic.

terry says

where is shorty harris’s grave?

Tami says

In Death Valley, about 20 miles from Furnace Creek. You have to access it from the south side as the road is closed by Stovepipe. You should be able to find in on Find a Grave of Historical Marker Data Base.

Bill Selling says

Thanks for awesome read of some amazing history!!! Always enjoy your posts!!!

Tami says

Glad you enjoyed it!

John Harmon says

Love Rhyolite ! Been there several times over the last few years ! The train station is especially nice ! Would it be too commercial to stick a museum/ gift shop/ coffee shop in there? It would bring in more money, but also more people ! Your stories and photos are always so interesting ! Austin is a lucky cowboy !

Tami says

I would love to see the train station as a museum and gift shop; food would be great even if it was pre-made. They could use it to fun restorations. Sadly, I think Rhyolite lost a building last year.

My husband is very thankful that Austin keeps me entertained and is such a great traveling partner.

John Harmon says

We will be there in mid May, heading up from Needles ! Hope to stop at a couple ghost towns and sagebrush saloons on the way !

Tami says

Sounds like a fun trip!