The Children’s Village at Manzanar is a forgotten piece of American WWII history. The US Government removed children of Japanese descent who did not have parents able to care for them and forcibly relocated them to the Manzanar Internment Camp.

While incarcerated, the children attended school with the general population. Other children often ostracized them outside the classroom, leaving the Children’s Village a camp within a camp. Having come from institutionalized care, their day-to-day routine remained primarily unchanged. For many, the most challenging time came with the camps closing, when release separated them from the only family they knew.

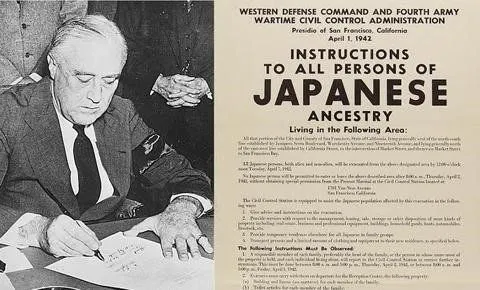

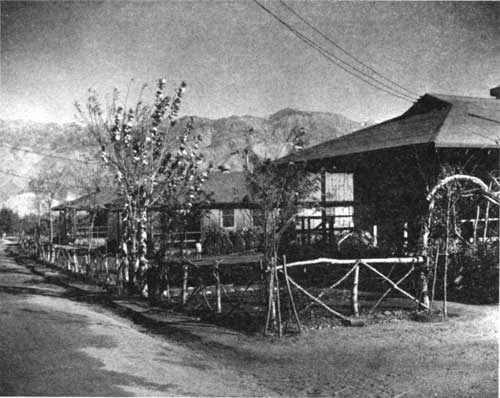

War Relocation Centers

(Photo credit: Stones That Speak)

In early 1942, only months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 to “any or all persons” of Japanese descent, removing them from prescribed military areas on the West Coast. The order created ten war relocation centers for the banned individuals.

(Photo credit: Densho)

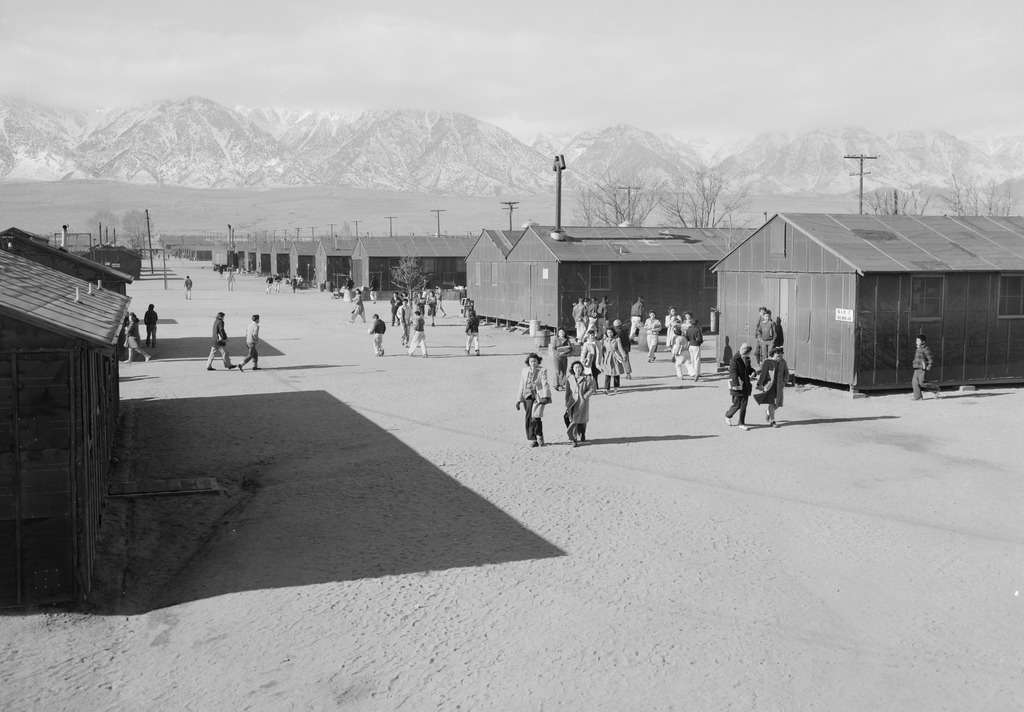

Over 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent, men, women and children, were forced to abandon their personal property and move to the military-style camps. Two-thirds were native-born Americans, and the US Government denied many others citizenship under federal law.

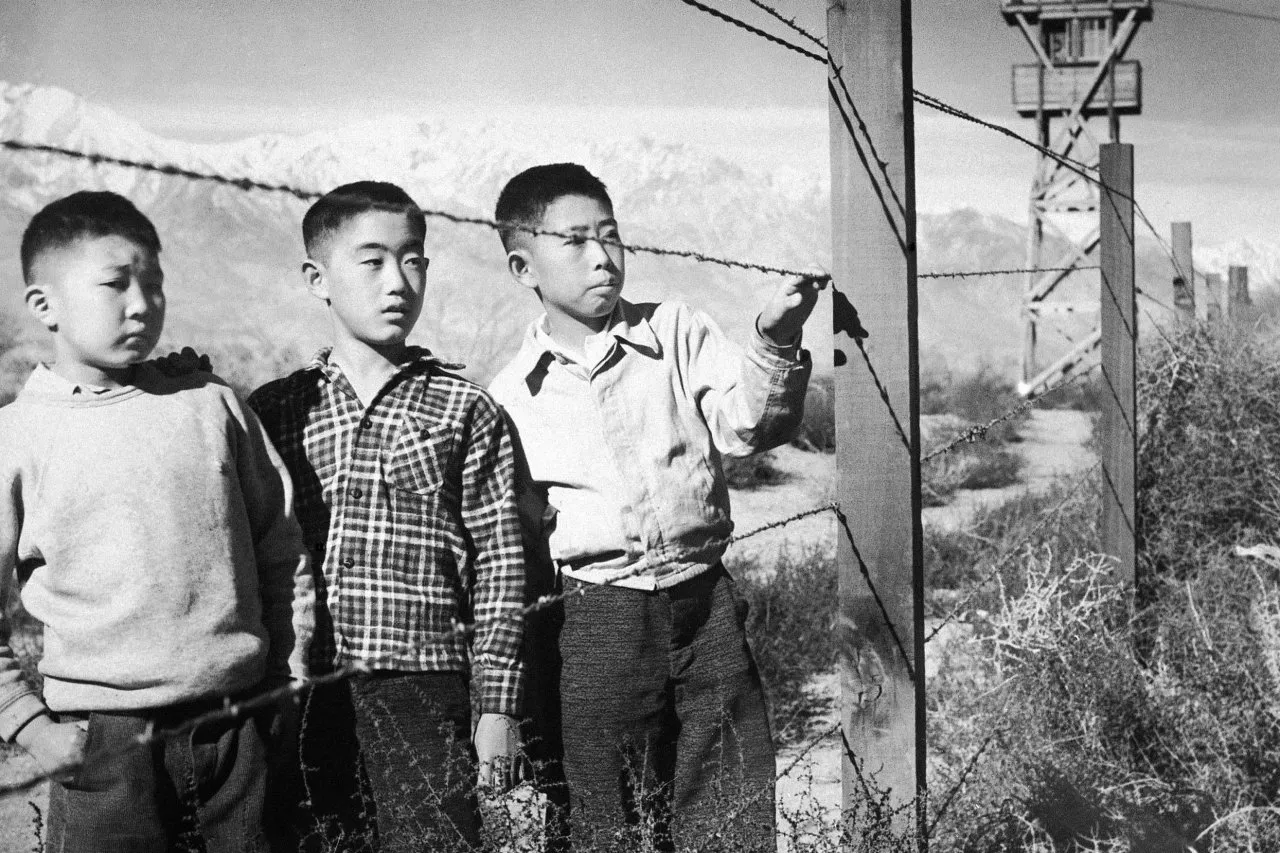

Manzanar was the original internment camp to open; the first detainees arrived in March 1942. By July, the camp incarcerated over 10,000 Japanese Americans, most from Los Angeles. The camp covered over 500 acres, fenced by barbed wire and surrounded by eight guard towers armed with machine guns.

Photo credit: Ansel Adams Library of Congress)

A 20-by-25-foot room was allotted to any combination of eight individuals. The only furnishings provided were an oil stove, a single hanging light bulb, cots, blankets, and straw mattresses. The barracks had no plumbing. Bathrooms had showers and toilets lined in open rooms, providing no privacy. Manzanar served cafeteria style in mess halls, often requiring standing for a long time and children being separated from their parents.

(Photo credit: Public Domain Wikipedia)

Despite forced incarceration based solely on their heritage, detainees created as normal of a town as they could, including stores, newspapers, beauty salons, beautiful water gardens, sports, and recreational activities.

Children’s Village Japanese Orphans

Before WWII, children of Japanese descent who didn’t have parents able to care for them lived with extended family, in foster care or 3 Japanese orphanages: Salvation Army Home in San Francisco, the Maryknoll Home in Los Angeles, and the Shonien in Los Angeles.

(Photo redit: National Park Service)

While many children were orphaned, some had parents who were ill, arrested following the attack on Pearl Harbor or were born to unmarried mothers. Officials combed through records, searching for any drop of Japanese blood. Tragically, at least one child was orphaned after their parents committed suicide in the internment camps.

(Photo credit: (Photo credit: Toyo Miyatake Library of Congress)

(Photo credit: Densho)

Shonein Assistant Director Lillian Matsumoto advocated for the children and staff to remain together as a family unit, leading to the creation of the Children’s Village.

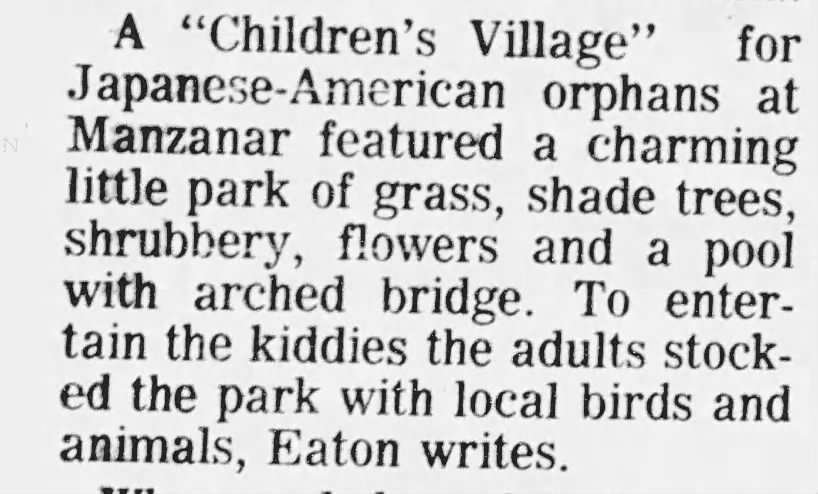

Mammoth Lakes, California · Thursday, November 12, 1970

Manzanar was the only war relocation center with an orphanage. Children aged newborn to 18 were taken from foster homes, orphanages and unwed mothers and placed in Manzanar Children’s Village. One hundred and one children, with a third under the age of 4, lived in barracks separated from the main camp.

(Photo credit: National Park Service)

As Manzanar had the only orphanage, children arrived from California, Oregon, Washington and Alaska. In June 1942, 61 children from orphanages and foster care arrived by bus at Manzanar. Eventually, 101 children would live in the Children’s Village.

(Photo credit: Toyo Miyatake Photograph Studio National Park Service)

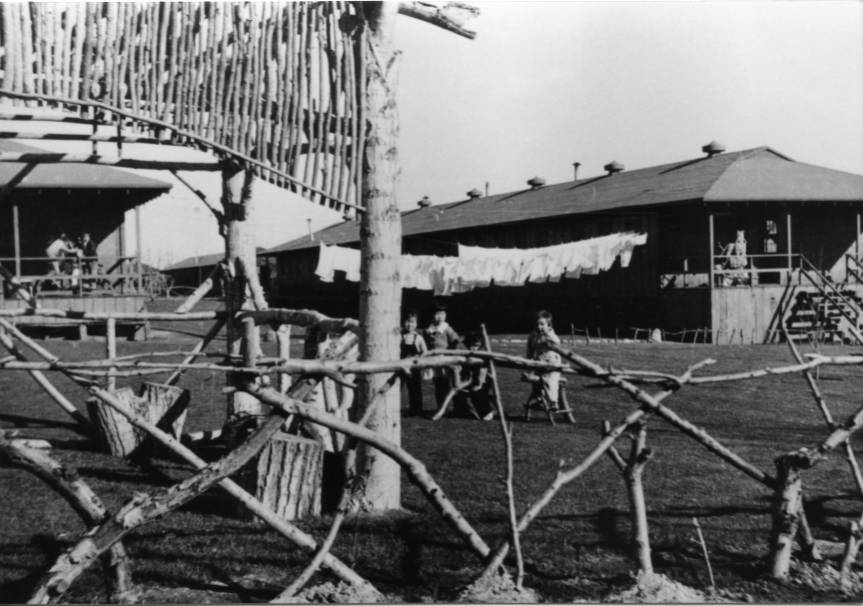

A camp within a camp

Children’s Village was a camp within a camp, part of Manzanar but separate.

Built on an old pear field across from the hospital, the Village consisted of 3 one-story buildings. One building was caregiver apartments, a recreation center, a kitchen, and a dining room. The second building housed infants, young children, and girls; the third was for boys and a storeroom. Unlike the family barracks, Children’s Village had running water and bathrooms. As many of their orphanage staff, including cooks, moved with them to Manzanar, they had better food than the rest of the camp and had dinner together as a family unit.

(Photo credit: California State University, Fullerton)

The Village had lawns, trees and flowers. The staff built a playground and gazebos. Some residents of Owens Valley baked the children cookies and brought them clothing and toys.

Approximately 3,000 children were enrolled in school while incarcerated in Manzanar. The elementary school enrolled 1,300, and the secondary school enrolled 1,400. Students from the Children’s Village attended classes with the general population.

(Photo credit: National Archives)

The children’s orphanage routine remained unchanged as they came from institutional care. The orphans attended the Manzanar school but were otherwise separate from the other children. Many of the children from Manzanar were ostracized by children from the Village whose parents didn’t allow them to socialize outside of school. One positive of the isolation is that the children were more protected from illnesses that ran through the overcrowded Manzanar.

(Photo credit: Ansel Adams, Library of Congress)

Manzanar Cemetery

Over 145 individuals died while incarcerated at Manzanar, including 17-year-old James Ito and 21-year-old Jim Kanagawa, who were shot and killed in the “Manzanar Riot.”

Many of the deceased were cremated in the Buddhist custom. At least three children were buried in Manzanar cemetery: a stillborn and two premature babies from parents at Tule Lake Segregation Center.

A large concrete monument stands watch over the cemetery. The Japanese characters read “Soul Consoling Tower” on the front and “Erected by the Manzanar Japanese, August 1943” on the back.

Visitors leave paper cranes in remembrance, worship, and reflection.

Closing Manzanar’s Children’s Village

For many residents of the Children’s Village, the most challenging time came with the camp’s closing. The children and staff were the only family they knew. Many had spent their entire life in institutionalized care and never lived in traditional family units. The orphanages did not reopen following WWII, meaning the children would be separated when they were discharged from Manzanar.

(Photo credit: National Archives)

Half of the children reunited with one or both parents upon release. Others moved to group homes, and a handful were placed with foster or adoptive families. Children transition not only from institutional care but often to white families with no understanding of Japanese culture. Records for some children were lost, leaving a question about their legal guardians, which left them in limbo.

In September of 1945, the last children left the Children’s Village: Annie Shuraishi Sakamoto and Celeste Loi Teodor. When they arrived at Manzanar, Annie was three years old, and Celeste was five; both were moved into foster care with the camp closure.

Ralph P. Merritt, Manzanar’s top official, in his final report of the internment camp in 1946, wrote

“The morning was spent at the Children’s Village with the 90 orphans [to date] who had been evacuated from Alaska to San Diego and sent to Manzanar because they might be a threat to national security. What a travesty [of] justice!”

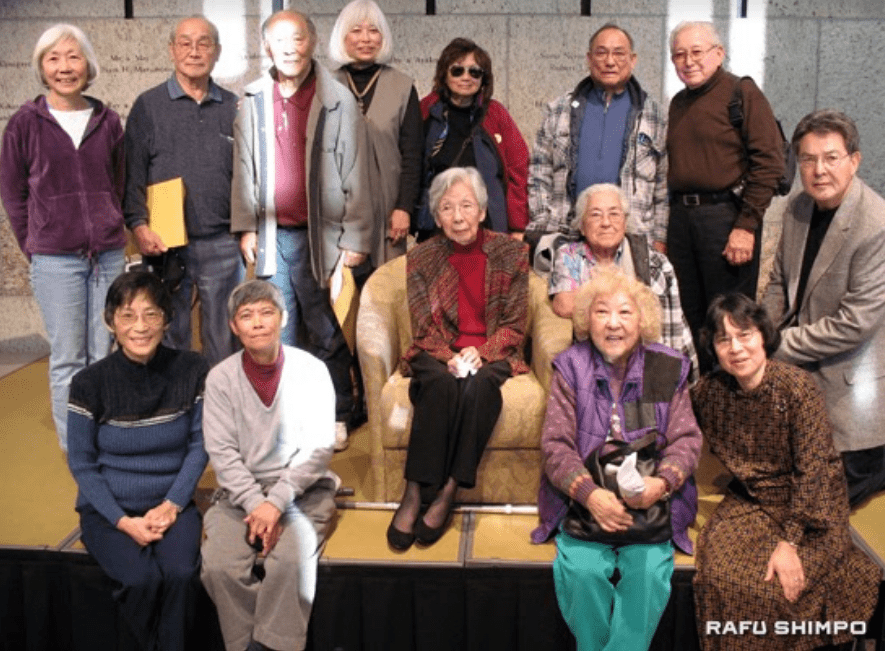

Lillian received the Outstanding Alumna award from the Japanese American Women Alumnae of UC Berkeley

(Photo credit: Rafu Shrimpo)

WANT MORE GHOST TOWNS?

For information on more than five hundred ghost towns in Nevada & California, visit the Nevada Ghost Towns Map or a list of Nevada ghost towns.

Learn about how to visit ghost towns safely.

References

References

- California State Portal: Correspondence on Closure of Manzanar Children’s Village

- Densho Encyclopedia: Manzanar Children’s Village

- Evening Vanguard: Varried tasks occupy Manzanar colonists. August 7, 1942.

- Irwin Catherine. Twice Orphaned: Voices from the Children’s Village of Manzanar. California State University Fullerton, 2008.

- Japanese American National Museum: Orphans

- Manzanar Committee

- Mono Herald and Bridgeport Chronicle-Union. Three thousand crates of product produced. September 3, 1942

- Monterey Bay, California State University: Orphans of Incarceration: Manzanar and The Children’s Village (Episode 11)

- National Park Service: Foundation Document Overview; Manzanar Historic Site

- National Park Service: Manzanar Children’s Village

- Wikipedia: Manzanar Children’s Village

David Sadewasser says

Very poignant story, Tami.

I had a coworker whose parents had been interred in a camp in Wyoming. He (the coworker) had difficulty describing the stories his parents told him. Still saddens me to this day. Never forget.

Tami says

I was surprised how many people didn’t know about the camps. Growing up in Idaho, we had a lot of Japanese descendants who settled there after being released.

Interestingly, my friend’s father was in Salt Lake City, so outside the exclusion zone. He wished he had been in a camp because the discrimination he faced.

Rebecca Manning says

Great write-up, Tami!

Thank you for such a stirring read….

When I was a little girl, (lived aboard NOTS from ‘49 -‘67), we would go pick apples from the trees.

Those trees survived without care for years! Finally the apples were too sparse, tart and tiny, so my

mom said,”No more, we will leave the ghosts alone now.” 😢

Tami says

Powerful story.

They are bringing back the fruit orchard.

Tim says

Really well writen artical on manzanar i did not know they provided a special place for the children. We visited back in the 90s and at that time all there was was the auditorium there were no other structers. Also across the HWY was a concrete run way used by the military for supplies.

Tami says

The park and volunteers have done a lot of work, especially the last few years. The gardens are a priority and are beautiful.

Christensen says

This was one of the greatest violations of the Constitution of the United States 🇺🇸 during World War ll ! Absolutely shameful to this day!

Chuck says

It’s crap like this that makes me ashamed of my Government!

Roosevelt and his administration did horrible things the the American Japanese in the name of “safety”

Chuck says

Thanks Tami, well written, most interesting … look forward to each story you post!

Tami says

I’m glad you ejoyed it. Sad part of history, but it needs to be remembered so we don’t repeat our past mistakes.