The Nevada Insane Asylum opened in 1881 to care for Nevadans who were unable to care for themselves. Funding and staffing issues plagued the hospital, causing patients to be lost in the system. For almost 70 years, patients who died were buried on hospital grounds. With the abolishment of hospital cemeteries, the graveyard was forgotten. Multiple construction projects desecrated the graves; Friends of Northern Nevada Adult Mental Health Services Cemetery fought to have their memories preserved.

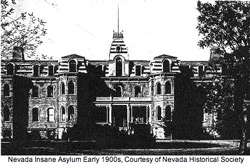

Nevada Insane Asylum

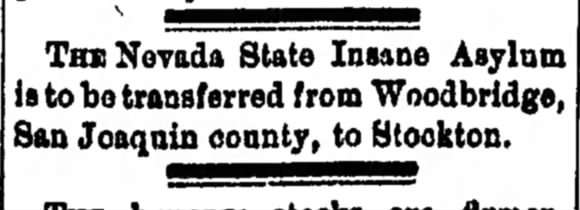

In the late 1800s, Nevada lacked the facilities to care for those with mental health issues. Nevada contracted with several hospitals in California to house the Nevada Insane Asylum. They first sent patients to Woodbridge in San Joaquin County and later to the Pacific Asylum in Stockton.

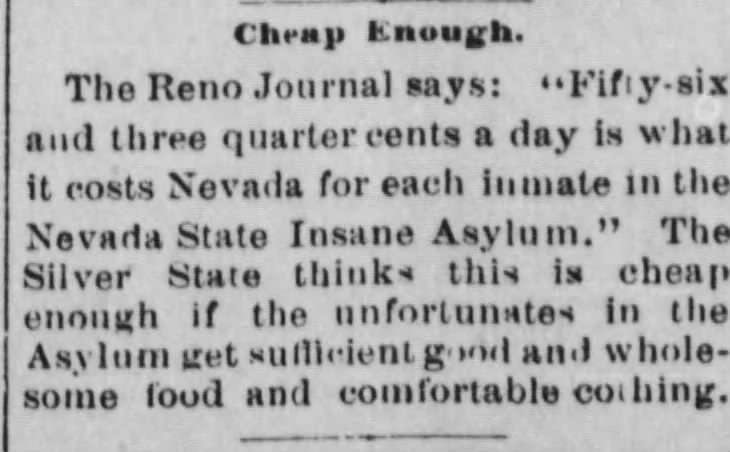

Nevada believed the desert climate would be better for patients. More importantly, they thought care would be more cost-efficient in Nevada. The cost was deemed “cheap enough” at $0.56-3/4 a day.

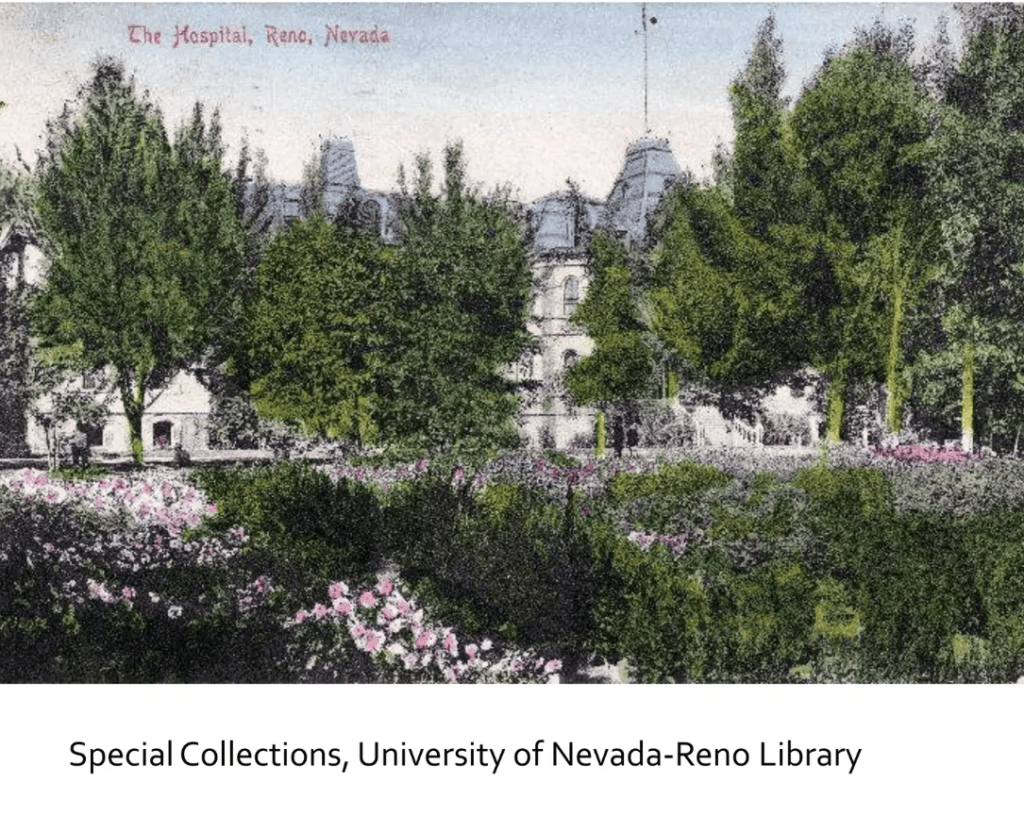

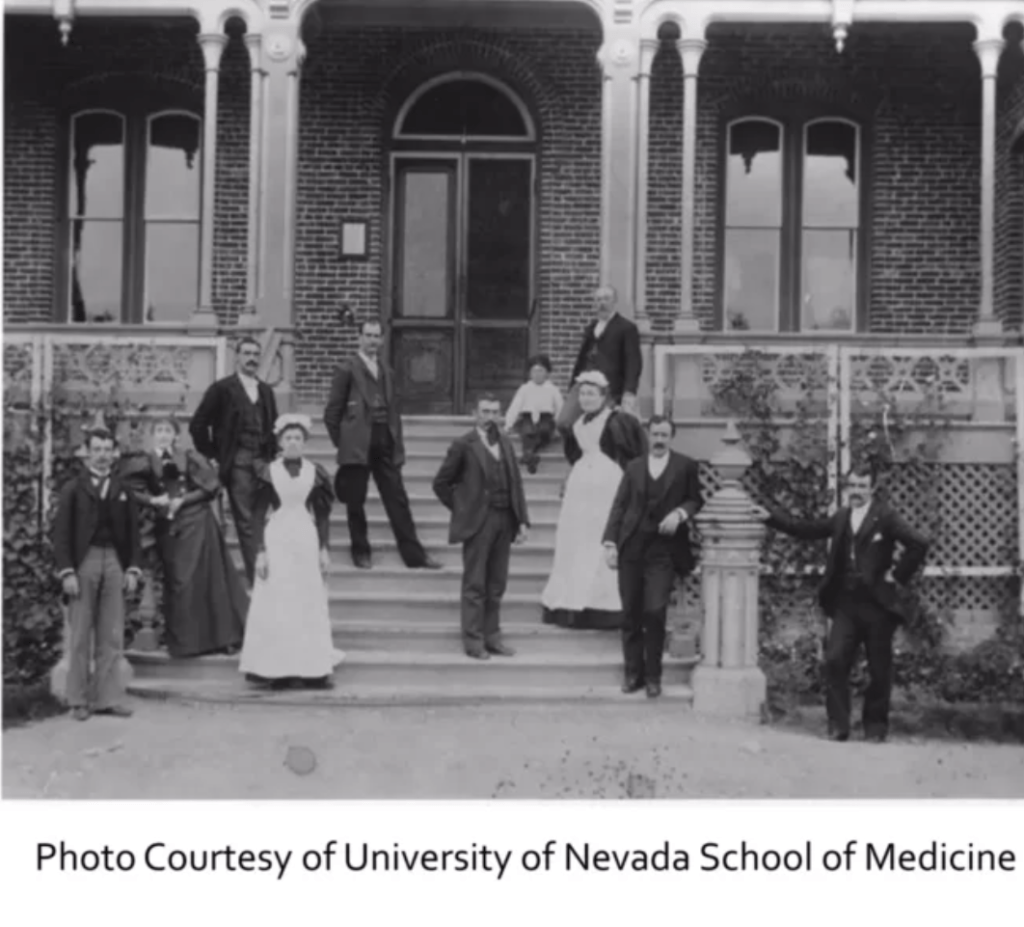

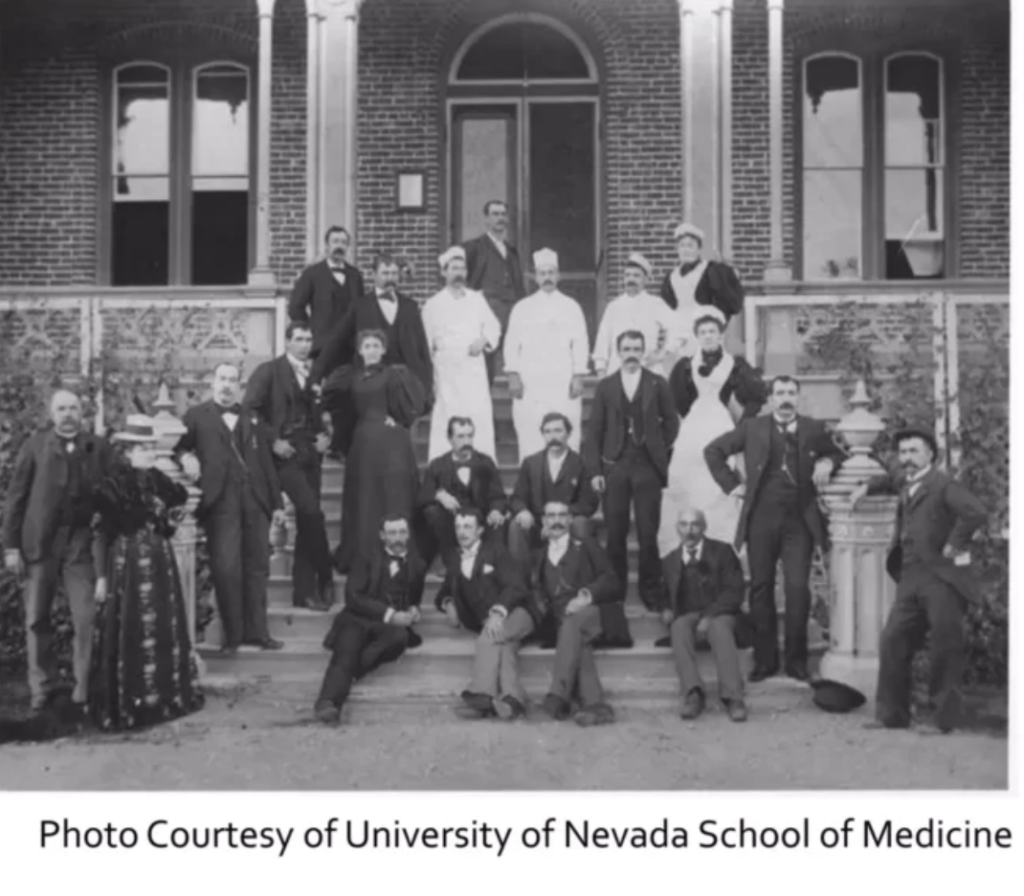

Ninety-two acres outside of Reno were deeded to create a state hospital. The facility opened in 1881 as the Nevada State Insane Asylum. The main building was four stories and 232′ by 46′ with two wings of 100′ by 46′. Morrill J. Curtis designed the structure. Each floor consisted of two wards. Three boilers heated the facility, which included six dining rooms and a recreation room. The hospital had indoor plumbing, including nineteen bathtubs and sixteen sinks. Every room had ventilation, including a “foul air outlet” and fresh air intake.

The first patients arrived by train from Stockton on July 1, 1882. The patients were residents of the state who Nevada who had been housed in California. The 148 patients, 117 men and 31 females, arrived on a special train. Patients were referred to as “inmates.”

About half the town will be down to the asylum this morning to see the crazy folk come in.

The Journal (From Friends of Northern Nevada Adult Mental Heatlh Services Cemetery)

The asylum operated similarly to a Poor Farm, with the residents raising crops and livestock and operating a dairy. They provided for the hospital’s needs and sold excess. They raised hay, vegetables, eggs, milk, potatoes and even tobacco.

The counties sent “old, harmless, incurable, idiotic and imbecile patients” to the asylum to alleviate their responsibility for caring for disabled residents. Soon, the hospital was overcrowded, with 196 patients in a facility designed for 160. In 1895, the legislature approved funding of $15,000 to add an annex.

The Stone House was added in 1890. It was the superintendent’s house and was later used by workers in the male ward. The stones were repurposed from what was planned to be the Nevada State Prison, north of the hospital grounds. The 450′ by 500′ prison “Great Wall” was started in 1873. By 1875, three walls had been completed, but the new legislature decided they wanted the state prison in Carson City. Ironically, the top layers of stone walls were quarried from what became the grounds of the Nevada State Prison in Caron City.

Fourteen children were sent to the hospital. They were cared for by patients with “strong mothering instincts.” The children were “physically deformed and uneducable.” Only a few dolls and toys were present. Children were moved to the adult wards when they turned twelve.

The community could visit the asylum anytime with complete and unrestricted access and judge the care for themselves. The invitation may have been well-meaning, but sadly it drew an audience of voyeurs.

Part of the treatment was normal society activities, such as dances on Saturday evenings. Mary Stoddard Dolten (wife of famed author Alfred Dolten) reported the patients were wonderful dancers and very mannerly. She proclaimed the hospital a “Model institution of its kind.”

By 1891, the facility had started to decay. The poor conditions of wood planks in the well caused illness among the patients.

Dr. Henry Bergstein was appointed head of the hospital in 1895 in honor of his political service to the governor. He made progressive changes at the hospital in his three years of service. The name was changed to the Nevada Hospital for Mental Diseases; he stopped allowing visitors to “gawk” at patients and recommended legislation that sent the poor who are not mentally ill to the hospital.

Funding was inadequate for staffing or repairs. Only eight staff attended to 190-200 patients. Funds were taken from patient care to repair broken plumbing. In the early 1900s, the hospital required employees to work 12-hour days, six days a week and live on the grounds for $55 a month.

The Forgotten Patients

The hospital admitted patients for various mental health diagnoses: melancholy (depression), dementia, and chronic mania (bipolar disorder). Other reasons for admittance included losing a business, bad air, lack of food, death of a husband, ardent spirits, “uterine diseases,” and the inability to get along with others. Many patients likely had health conditions related to mining.

Admitted 1917 until her death on February 15, 1943

(Photo credit: Friends of Northern Nevada Adult Mental Health Services Cemetery)

There are multiple tragic stories of the hospital’s patients. Cora Wilcox Clark was admitted to the hospital by her husband as he couldn’t get along with her. Her family corresponded with Cora and sent funds for her care and clothing. Trying to visit Cora, they were told she vanished, even though the hospital had continued to accept funds. Several years later, a death certificate showed she died in 1943. Instead of her family having the option to inter her at the family grave, she was buried in a paupers grave.

Stacy Severn Tinkham’s parents left their large estate to the hospital for care, burial, and a headstone for their son. They died in 1903 and 1906 and left instructions for their son to be buried next to their graves at Mountain View Cemetery in Reno. It is unknown what happened to the trust funds. Stacy died on August 21, 1934, and was buried in an unmarked grave at the hospital.

The original hospital building was demolished. Later structures remain and are now part of Northern Nevada Adult Mental Health.

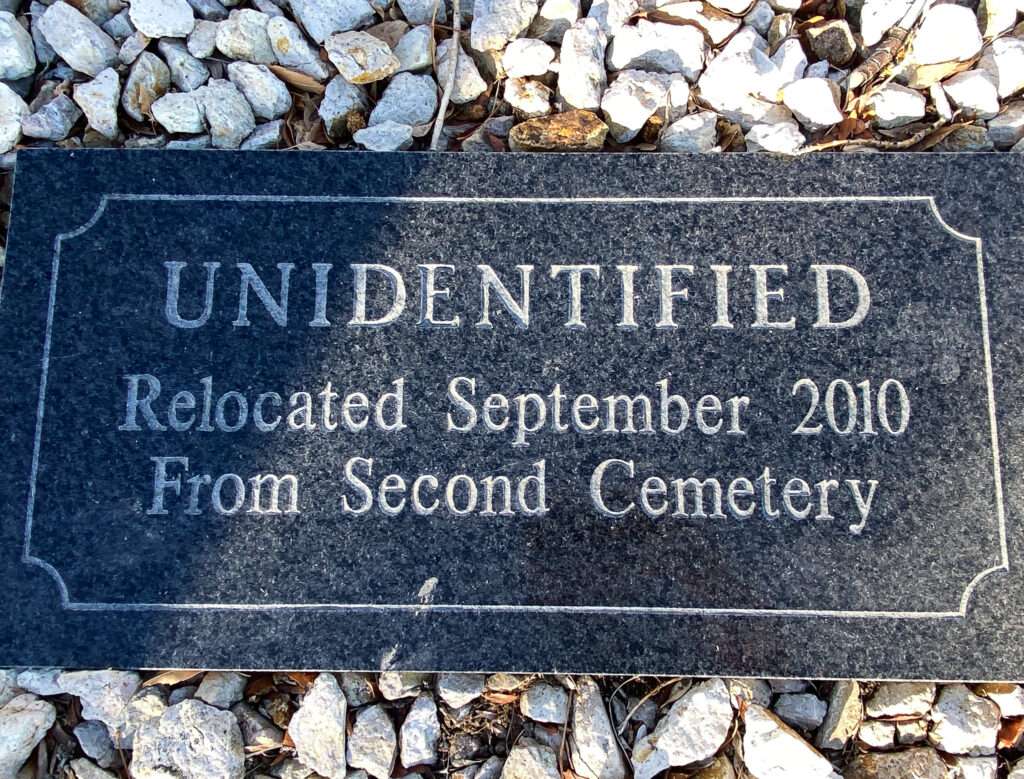

Nevada Insane Asylum cemetery

While the hospital discharged some patients, many remained until their death, and the hospital buried them on the grounds.

Employees handled the burials. There was little ceremony and crude wood caskets and shallow graves. Markers were simple tin plates. Interments occurred under the cover of darkness when patients were in their rooms.

The first death at the hospital occurred on September 7, 1882. William R. Place, aged 42, died of Bright’s Disease (nephritis). He had been a resident of Esmerelda County, and his brother attended the burial.

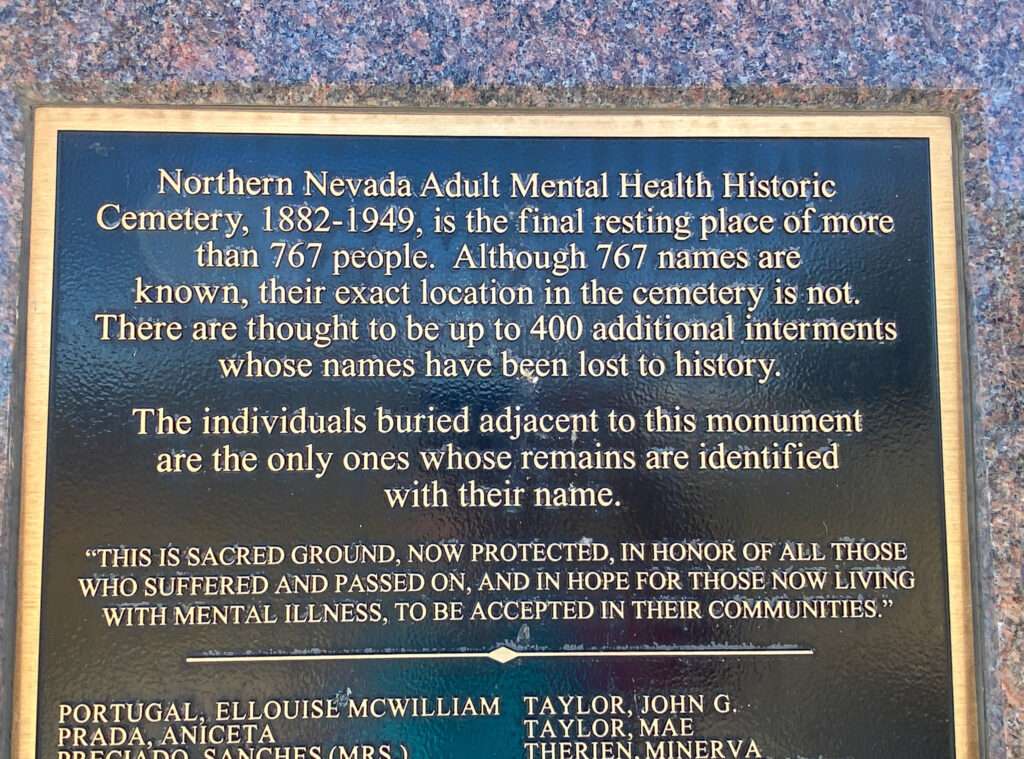

The last burial occurred in 1949. As many records were lost, there is no exact number of how many were interred at the cemetery. The hospital buried at least 767 souls in the cemetery, but there are thought to be an additional 400.

In 1949, the Nevada legislature passed a bill to “abolish the use of any cemeteries now located on hospital grounds.” While the law prevented new burials, it made no accommodations for the present graves. As a result, it was as if the entire cemetery was erased from history.

In the 1940s, a large ditch was dug through the cemetery. With the knowledge of the state, an excavator dug the 6′ wide and 8′ deep trench.

…a large pipeline was installed through the cemetery and several of the graves were ripped apart and the remains were later shoved back into the excavation to become backfill.

Dennis Cassinelli: Rededication of the Historic Asylum Cemetery

Over the years, multiple construction projects unearthed bodies and caskets. Graves were relocated multiple times. Grave markers, when present, were lost and switched. Boundaries to the cemetery were lost. Parking lots and a kitchen were built on hallowed ground.

In the 1960s, the cemetery’s grounds became Pinion Park Playground. In 1977, children unearthed bones while playing. Strangely and disturbingly, the cemetery is now a park with an exercise area, pathways and shelters. Dogs are allowed; while there are bags and receptacles for dog waste, owners did not pick up after their animals in several cases.

Remembering the forgotten patients

In 2008 an inquest was made into Cora Wilcox Clark’s burial location. Family members, citizens, and historians began researching the hospital and cemetery. Friends of Northern Nevada Mental Health Services Cemetery was created to property memorialize those buried there. Legislation was introduced in 2009 to designate the grounds as a historic cemetery. On May 29, 2009, Governor Gibbons signed SB 256, creating a historic cemetery.

The new cemetery boundary was dedicated on January 12, 2011.

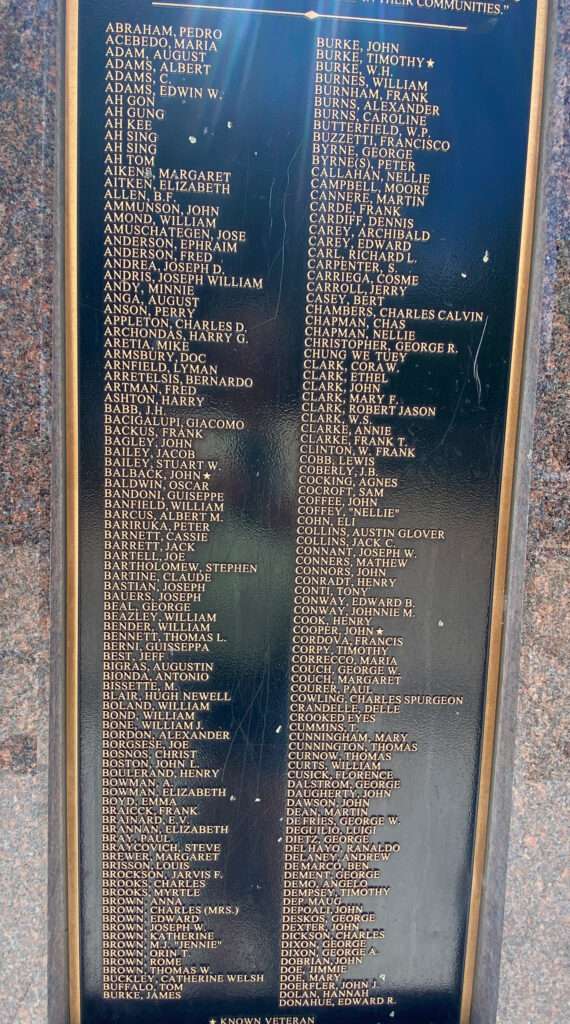

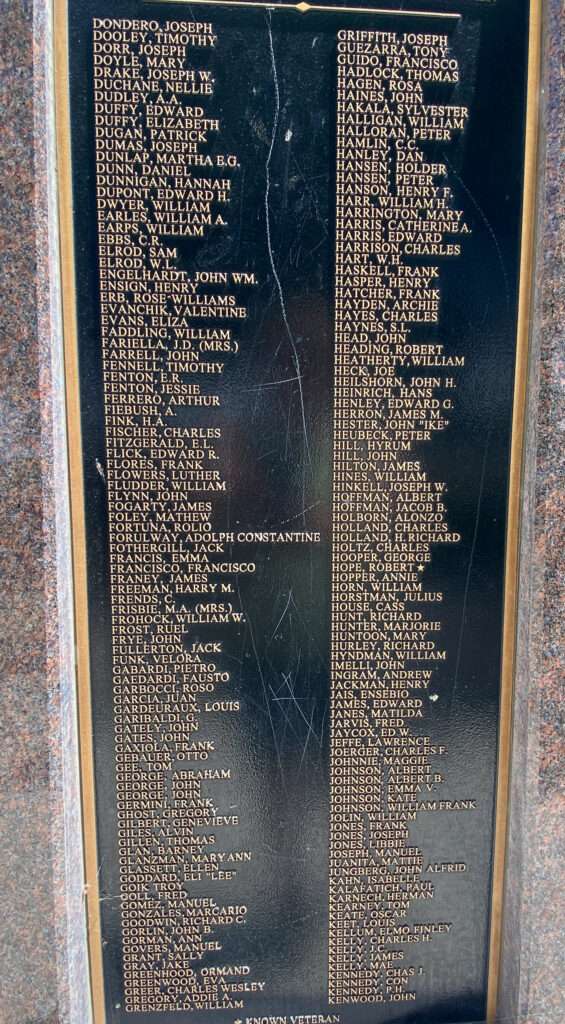

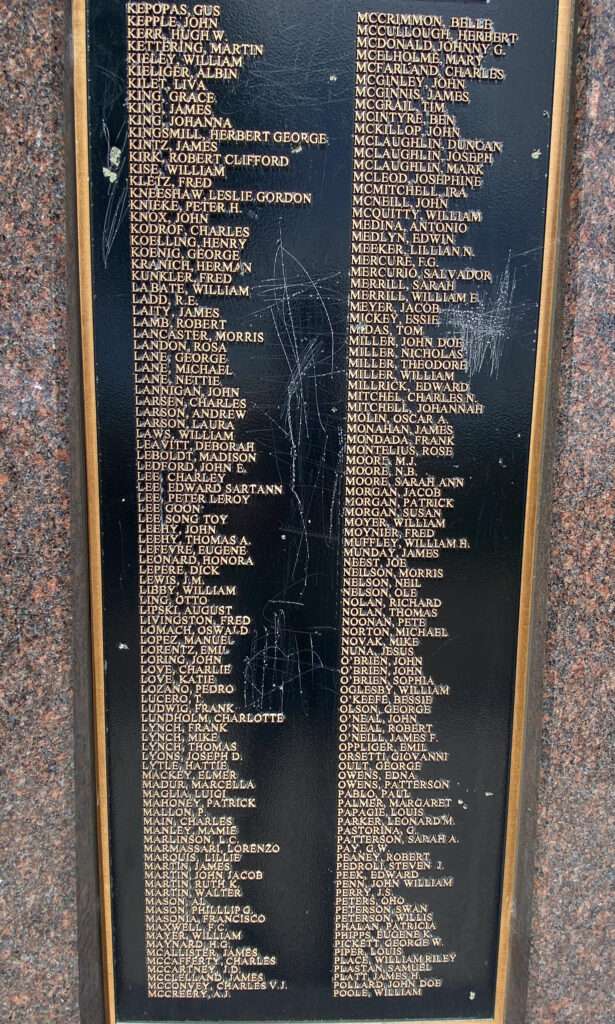

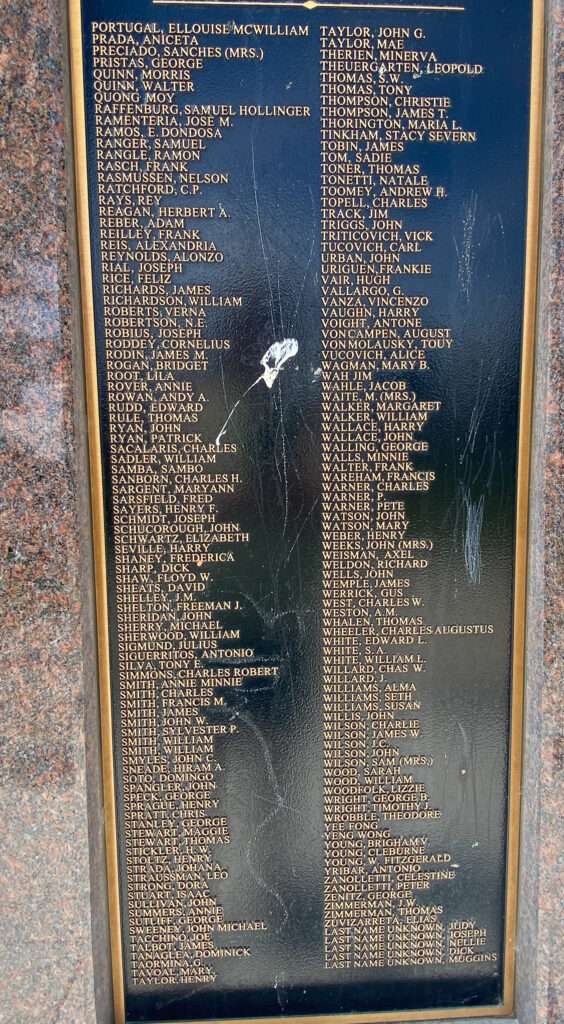

An obelisk memorial stands in remembrance of those forgotten. Each side has the same memorial and a list of the 767 known to be buried at the cemetery. Sadly, with the lost records and relocation of the graves, most grave sites are unknown.

Thankfully, understanding of mental health issues has grown by leaps and bounds. Asylums and long term hospitalization have given way to outpatient care or short-term hospitalization. We can not undo the past, but we can remember those lost and honor their lives.

WANT MORE GHOST TOWNS?

For information on more than five hundred ghost towns in Nevada & California, visit the Nevada Ghost Towns Map or a list of Nevada ghost towns.

Learn about how to visit ghost towns safely.

References

References

- Dennis Cassinelli: Rededication of the Historic Asylum Cemetery

- Friends of Northern Nevada Adult Mental Health Services Cemetery

- Historic Reno Preservation Society: Nevada’s Early Mental Health History; The Buildings

- Julia Bulette ECV: Remembering Reno’s Lost Patients

- Nevada Geneology Trails: Nevada State Asylum 1886 Records

- Nevada Historical Society Quarterly: Nevada’s Treatment of the Mentally Ill 1882-1961

- Washoe County

- Weekly Nevada State Journal, May 19, 1877

- The White Pine News, August 16, 1884

Daniel P Prall says

Wow. How sad. 😢 just a terrible tragedy from day 1. Things were sure different then. What was socially acceptable then is abhorrent today. Thank you for the research and the time it took to put all this together. My heart breaks for those poor souls. I’m positive the care they received was very subpar. Then to end up forgotten in a potters field. How terrible. Not all Nevada history is silver and gold.😓

Tami says

It was difficult not to go into the treatment, that could be an entire book. Even the admitting diagnoses are a huge rabbit hole, what we would consider normal now could land you in the hospital.

Nevada wasn’t ideal, but it wasn’t bad for the time.

Your last statement is so true. I say some parts of the good old days, weren’t so good.

Douglas Pachnik says

As a kid in the 80’s I use to play in that park (now historical cemetery location) unknowing what laid below the surface of the ground. It remained a park well after I got out of high school in the mid 90’s. Looking back I did feel uneasy when I’d go there in the evenings to think and get away from my parents and the house for a bit.

Tami says

It is so strange that someone put a playground over a cemetery. Then, a dog park. I won’t be surprised if more bones are dug up. I can’t imagine those kids and parents finding a body.

Clora Clark says

I wish someone would find my bones.